No Place for a Lady? Back to the Victorian Penal System

The reforms proposed by Justice Secretary Chris Grayling filled news headlines today. His objective is clear. To make prisons, tougher on inmates, and therefore no longer a ‘reward’ for those who break the law. The reforms that will come into effect later this year are predominantly aimed at male prisoners – the fate and consideration of their female counterparts left for another day. Historian Philip Priestley’s adage that ‘Prison was a man’s world; made for men, by men. Women in prison were seen as somehow anomalous: not foreseen and therefore not legislated for’ seems just as applicable in light of today’s announcement, as it does for the period he writes about – the Victorian. The reforms proposed today will in fact take place in many of the same institutions – and even buildings – created in the nineteenth century to tackle the very same problem ministers argue about today; Those most recognisable bastions of Victorian penal reform – Brixton, Pentonville, and Strangeways to name but a few.

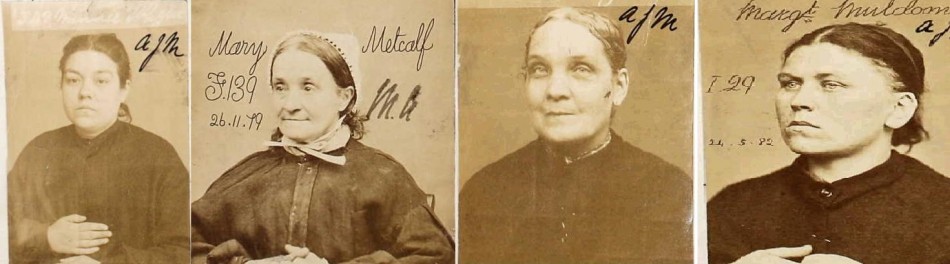

The image of the Victorian convict prison has been enshrined in popular fiction and historical accounts alike. It is no doubt some of these representation that inform many of the ministerial decisions taking place today; A harsh unrelenting system of reform, punishment and self-reflection; An institution that brutalised the body to civilise the mind.

A short historical perspective has perhaps blinded many of us to the fact that when these institutions were created the early part of the Victorian period, the modern penal system (still in place today) was trying to make the experience of criminal justice, and undergoing punishment not more unpleasant for those at its mercy, but less so.

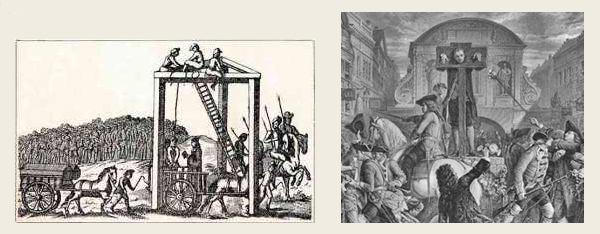

The ‘Bloody Code’ of the eighteenth century is a period in English criminal justice history that is in many ways more notorious than either its nineteenth or twentieth century equivalents. The iconic images of Tyburn’s gallows, of any local pillory, or the chaos of the infamous Newgate gaol help us to vividly imagine a brutal legal system so unlike our own.

The justice dispensed prior to the nineteenth century cared and catered little for the age, gender, or vulnerability of offenders, only for the perceived guilt or innocence of the accused. The corporal and (in some severe instances) capital punishment of children – for what in many cases could be subsistence level crimes – is the most famed and unsettling legacy of this system. But perhaps more sinister even than that was the social and cultural experience of being incarcerated in a pre Victorian prison such a Negate or the transportation hulks. Gaols such as this acted not as institutions that dispensed punishment and strove to reform offenders, but instead of holding pens – a place to detain criminals until they could be brought before the court, or after their conviction until their sentence – to be whipped, transported or hung for example – could be carried out. These ‘lock-ups’ mixed men women and children together in a series of shared cells. The conditions of these places not only lacked basic hygiene standards, but ultimately left inmates vulnerable to abuse, exploitation and sexual violence. These were institution renowned for corruption, money rather than need determined an inmate’s experience.

Developing Victorian social sensibilities – particularly those concerning gender – saw traditional processes of the legal system come under scrutiny, and the institutions prevalent during ‘the Bloody Code’ give way to those modern penal institutions that still service the justice system today. These institutions aimed not just to punish, but to civilise, humanise, and reform the prisoners within. Whilst Victorian society had labelled women the gentler, weaker sex, and fully acknowledged their inability to withstand the same interactions with the world that men undertook, the prison systems of Victorian England catered little for the difference between male and female prisoners.

Alongside some specialised regimes such as the separate and silent system – where prisoners were discouraged from communicating with one another, so as to encourage self-reflection, and deter the formation of criminal friendships – most prison operated a points and class based system dependent on notions of rights, responsibilities, and privileges, much like the ‘new system’ Chris Grayling is suggesting currently. This system held the key to a prison inmate’s experience – what diet they were permitted, how regularly they were allowed to write letters or receive visits, if and when they were permitted to socialise, what work they carried out, and what money they might receive on leaving prison.

Sarah Jane Swann’s penal record indicating she was in the ‘Star Class’

Sarah Jane Swann’s penal record indicating she was in the ‘Star Class’

Sarah Jane Swann’s points record for 1881

Sarah Jane Swann’s points record for 1881

Other commonalities of the prison regime were the use of uniform to strip prisoners of their former identity, and long days of laborious work, to punish the body and occupy the mind – for women, examples include fourteen to sixteen hour days in the prison laundry.

Throughout the Victorian period, and well into the twentieth century, debates about Prison regimes, prison reform and the welfare of prisoners raged. With every gain made for better treatment of prisoners, staunch opposition was raised complaining of lessened deterrent for wrongdoers.

Yet the changes that did take place over the period were the real victories of the Victorian prison system. Developments for female convicts included the education of prisoners, the provision of proper medical care, nurseries that allowed mothers to maintain contact with their children should they give birth in prison, and most importantly, refuges that acted as a stepping stone between incarceration and freedom – striving to place women in employment once they were released.

It was the facilitation of a life outside of prison, that saw women (and men) most commonly cease to offend. It was by humanising them, not brutalising them, by offering hope, not despair, that prisoners could be turned back into people.

The Victorian prison system was far from perfect. Despite continuous reforms, it cannot have been a pleasant place to be – perhaps that is its appeal as a model for modern government policy.

Instead of looking back to the Victorian ‘golden age’ of penal reform and coveting some of the the worst aspects of this; the uniforms, the hard labour, the points systems, and the restrictive daily routines, perhaps it might be of more use to ministers to consider the wisdom of previous penal reformers and prison philanthropists instead. These individuals and organisations came to understand that it is by improving the quality of life and living for those most desperate and disenfranchised in society – those most likely to offend – that we reduce the rate of crime and most importantly, recidivism. No matter how unpleasant you make the experience of prison, until you improve opportunity and quality of life on the outside, there will always be inmates aplenty to fill the cells.

This is a great post. When looking at the history of suspended sentences in Australia and the UK, I found that trying to ‘protect’ women (and children) from the horrors of prison was a significant part of the discourse on Victorian and Edwardian reforms in this area. The woman as a first, but serious, offender was used in several speeches by politicians during debates on ‘Probation of First Offenders’ legislation between the 1880s and the 1910s in both countries. Indeed, the Victorian penal system was seen as ‘no place for a lady’.

Hi Evan – glad you enjoyed it. I think the contemporary debates surrounding ‘what to do’ with criminal women are really interesting, and I think Priestly is right when he suggests that ultimately an inability to reconcile Victorian notions of femininity with the processes of the modern penal system saw female offenders little legislated for, and not really provided for as a separate group of prisoners – particularly at the beginning of the period. Although the the changes later in the period really show the penal system attempting to re-feminise female prisoners. Have you noticed any big differences between the U.K and Australia in terms of the rhetoric concerning or experiences of female prisoners?

Pingback: Strangeways Here We Come (again) | "The Worst of All Drunkards"

Pingback: Prison Punishment Records: The Price of Penal Servitude | WaywardWomen