A new book . . . and a new collection of wayward women

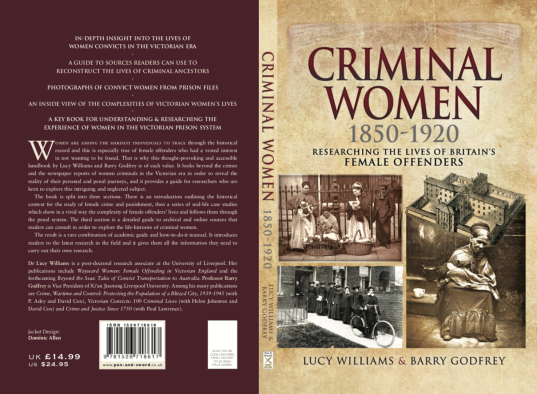

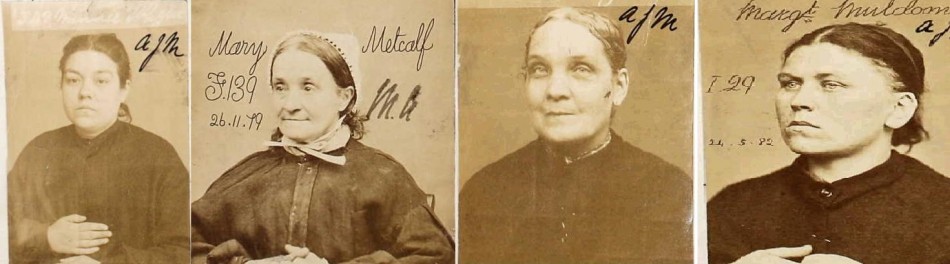

I’m thrilled to announce the publication of a new book, co-authored with my colleague Professor Barry Godfrey. Criminal Women 1850-1920: Researching the Lives of Britain’s Female Offenders has given me a wonderful opportunity to dive back into the world of Wayward Women – with a bit of a twist.

Our book presents a rich collection of in depth case-studies of women who broke the law between the mid-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. We trace the lives of women during a remarkable time of penal and personal change. As their social roles were changing, and the state was exploring more ways of dealing with intransigent women than simply incarceration. From some of the last women to be shipped to Australia as convicts in the early 1850s, to girls wreaking havoc in juvenile reformatories at the turn of the century, and women imprisoned during the interwar period -a time still in living memory.

However, alongside these fascinating personal histories, we’ve sought to provide something extra too. Not only will readers find some contextual histories of women, crime, and punishment at the beginning of the book, but they’ll find a ‘how to’ manual in the final chapters. Our guide aims to help anyone discover and write their own biographies of criminal women, by exploring which sources are most useful for finding criminal women, and how researchers can get the most out of well-known material by reading between the lines, and connecting disparate dots of information together.

Writing Criminal Women has been a fun opportunity to jump back into the world of female offending, and a great reminder of just how rich and varied the lives, crimes, and stories of these women can be. With so many vivid cases to pick from, it’s impossible to pick a single one that represents the breadth of experiences we trace. Yet something many of our cases have in common is the ability to challenge our assumptions about the origins and trajectories of wayward women, and to prove just what remarkable histories lie waiting when we follow the right paper trail.

Violet Watson: Renegade, Runaway, Reformatory Girl

Not all children who ended up in reformatory schools were pint-sized pickpockets from broken homes, or violent unmanageable girls. Yet one thing all inmates had in common was the challenge they posed to authority – that of their parents, their communities, or the state. Something which did not necessarily end once they were locked away behind reformatory walls.

Violet Watson was born in Glasgow in 1896. Her father William was a photographer, who toured the country setting up temporary studios, or practicing street photography, to make a living. Violet’s mother, Mary, followed him and looked after Violet and her three sisters (and later two younger brothers).

Violet was a precocious child, who found the regime of her school too punitive for her liking. In 1909, at the age of fifteen, Violet played truant from school and left Glasgow for Perth, without notifying her parents where she was going. Upon arrival she began canvassing for donations to what she called the ‘School Revelation Fund’. She claimed she was doing so on behalf of her father who, once the sum of £50 had been raised, intended to challenge the Glasgow School Board about the harsh punishments they imposed on pupils. The scheme was, in fact, all Violet’s own. In Perth, a stranger purchased Violet a ticket for Aberdeen, to which she duly travelled and set up in the Bon-Accord Hotel asking visitors for donations.

Violet was quickly apprehended and brought to the police court where she was tried with impersonating an insurance agent, with the intention to defraud the public. In court it transpired that not only did Violet’s father have no knowledge of her plan, but also that he did not even have the money required to bring her back home to Glasgow. Instead, Violet was sentenced to spend three years in the Loanhead Reformatory for Girls in Edinburgh. A steep punishment for a youthful transgression.

Given that Violet found the regime at her school too harsh, it is no surprise that the reformatory was even less to her liking. As one of the older girls at the reformatory, Violet wasted no time in rallying fellow pupils to her cause. Less than a year after her arrival, in November 1910, The Scotsman reported:

Too young for prison Violet, not yet sixteen, was sent back to the reformatory she hated.

Less than two weeks later, Violet was back at the Edinburgh Sheriff’s Court, having affected another escape from the reformatory. Violet had somehow managed to procure money from inside the reformatory and had made her way to the station, travelling to Govan and then back to Glasgow. She was captured four days later and taken back to Edinburgh. The Sheriff vowed that everything that had occurred at the Dalry Reformatory would be ‘wiped out’ and that Violet, as ringleader of the insurrection, would not be allowed to return. She was sent instead to a reformatory in Sunderland, to be detained there at the pleasure of the secretary for Scotland. Violet was told that if she behaved in Sunderland, she would not experience further punishment. Furthermore, if her good behaviour continued, she might be released in just a few weeks.

The Sunderland Reformatory, c.1906.

The Sunderland Reformatory, c.1906.

Three months later, Violet was still in the Sunderland reformatory. Finding it no more to her liking that the Dalry reformatory and with release not forthcoming as promised, Violet made another daring escape. Climbing out of an attic window and onto the roof of the reformatory, Violet made her way down to the ground, and then scaled the perimeter wall, which had shards of broken glass fixed along its length. Violet made it over to the other side. However, she badly cut her arm in the process and left a trail of blood behind her. She made her way through Sunderland, begging strangers for help, and was eventually taken into a house to have her wound dressed. A local policeman had no trouble tracing Violet’s path, and she was apprehended just hours after her escape. Now sixteen, Violet could be held to the full account of the law. She was sentenced to two months imprisonment, which she served at Durham prison.

Prison was an even harder environment than reformatory school. Facing severe punishment for disobedience, and unable to escape, Violet had no choice but to serve her time. She was released in June of 1911 and, finally free of the institutions she hated, returned to Scotland. At the age of sixteen, she was not required to return to school, and so was free to build a respectable life for herself.

Violet was not typical of most girls who ended up in reformatory schools. She came from a respectable working-class family, she did not steal through poverty or want, was not violent or conventionally unruly. Her two years in the penal system occurred primarily because of her objection to the poor treatment of children by the institutions designed to cater for them. A complaint sadly not headed by those in authority. After her release, Violet married and settled in London. She was never convicted again, and as far as records allow us to know, went on to have a perfectly ordinary life with no hint of the teenage renegade she once had been.

Violet’s story is just one of thirty fascinating cases we explore in Criminal Women, just as a juvenile reformatory is only one of the many places we suggest to readers for finding their own tales of criminal women. With histories, case-studies, and a researcher’s guide to criminal, civil, and other resources, we hope that Criminal Women will inspire others to delve in to the world of female offending, and that it will be as much fun to read as it was to research and write.

Enjoyed reading Violet’s story, so many people do something stupid as a teenager that gets them into trouble, I wonder what it is that makes some people go onto live ordinary lives and those that become repeat offenders. Is it the environment they go back to or are some people able to make better life chooses that steers them away from that life. Looking forward to reading the new book.

Thanks for reading, Karl, I’m glad you enjoyed it. I also thought Violet’s story was an interesting change from the norm. I suppose its easy enough to forget that no two lives are the same, and neither are any two ‘criminal careers’. Usually the people who manage to leave trouble behind benefit from good support networks, decent opportunities for employment, and, not least, a bit of a break from society! Luckily Violet seems to have had some of those. Always nice to find a happy ending!

Loved reading Violet’s story. I was reading on an iPad and the paragraph on her escape from Sunderland and cutting her arm was repeated twice. Not sure if it was your side or my iPad.

Thanks Elizabeth – an editorial mishap on this end! Glad you enjoyed it nonetheless.

Dear Lucy, I am thrilled to discover your blog while researching for my novel set in Victorian Kent. I am thinking about buying one of your books and am wondering which one would be more useful to get an insight into prison life for women and how the actual process of being convicted and tried etc. went along. Do you also have upper class criminal ladies in one of them and do I learn something about, for example, what happened to their property? Thank you so much for helping!

Inga (from Germany, please excuse any mistakes)

Hi Inga,

Thanks for reading! I’d say either Wayward Women or Criminal Women could help with that. Criminal Women looks a little more in-depth at the prison and licence system, perhaps at the conviction process also but is mainly focused on working-class women (the majority of female offenders). that might be your best bet. However, Wayward Women looks more in-depth at crime has a few examples of middle-class offenders. You aren’t looking at the Penge murder by any chance are you? In terms of property, I can answer that here. The state would not have confiscated property in the case of conviction (unless it was stolen property, obviously) so the women would have to make arrangements for the safekeeping of money and other goods for the term of their incarceration. Hope that helps!

Yes, it helps so much!!! Thank you so very much, Lucy!!! I will look into your books more in detail and then decide. Maybe even both, ha! Thanks so much once more!!