An anonymous letter to Annette

As any writer who deals in biography or biographic histories will no doubt tell you – it is only too easy to easy to become emotionally caught up in the details of a subject’s life. The ups and downs and the twists and turns of an individual’s story are what makes them and their experiences human. The biography of female offenders has more than its fair share of heartbreak and outrage that speak to feelings as well as logic.The narrative of women that offended is littered with cases of illegitimate children, domestic violence, poverty, disadvantage and addiction.Even the coolest academic analysis probably, deep beneath the surface, had moments where sympathy or empathy clouded the bigger picture.

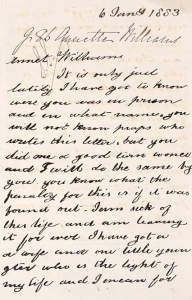

Occasionally a single piece of paper can return us poignantly and instantly to the people in our histories. A few words scratched in ink help us to remember that even for those how have left little behind there were whole lives full of complex friendships and chances taken or lost. A few lines have the power to transmit feelings of sympathy, sorrow, and hope across centuries.

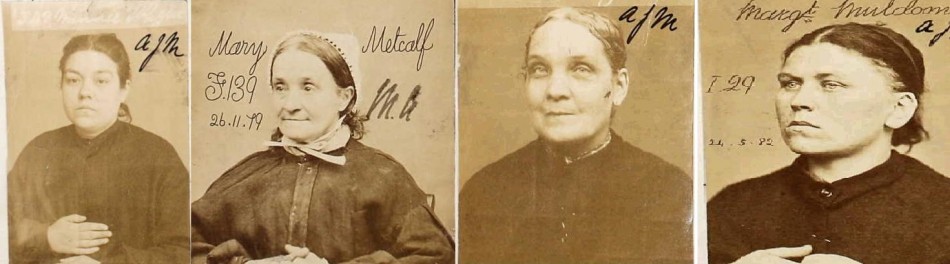

Annette Williams was a female convict in London during the 1880s. She, like thousands of others, has left only the lightest footprint in history. She was born, so she told prison officials, in Reading, Berkshire in 1850. Although there are no records to support this. Williams wasn’t even her real name. It was the last name of someone she had once burgled. She had no family that we know of or can trace to her. Annette cohabited with a man named James Hastings for almost nine years. She took his last name and the two were to all intents and purposes married. James was also an offender. Their relationship broke down in 1877 when after a joint trial Annette was found guilty and James was not. Annette had five recorded convictions over the course of her life, the last being a five year sentence in 1880 after a trial at the Old Bailey for burglary.

These sentences are the sum of what history has to show for the life of Annette Williams. There are a few facts that can be useful here, and a pattern of offending that contributes to how we understand crime in the period but nothing that really gives a sense of who Annette was or what her life was like.

On the very last page of her penal record, however, there is a letter. Quite ordinary in appearance and fairly short. Yet in just a few lines it has the capacity to give a more intimate glimpse into the lives of Annette and her peers than can ever be found for most.

The author does not sign his name and gives no address. No doubt he was himself an ex-convict or wanted offender keen to avoid detection by the authorities. The letter gave me pause for thought as it illuminated in simple worlds a dark world in which many like Annette found themselves trapped, the hope many convicts carried for redemption and a new life, and alternate lives in which women like Annette were capable of being remembered for their good deeds as well as their bad ones.

For this alone, it is worth sharing.

6 January 1883

Annette Williams

It is only just lately that I have got to know were you was in prison and in what manner. You will not know perhaps who writes this letter but you did me a good turn once and I will do the same by you. You know what the penalty for this is if it was found out. I am sick of this life and am leaving it for ever. I have got a wife and one little youngster who is the light of my life and I mean for her sake to struggle against myself and we sail for America next Wednesday. Are there no kind friends where you are that would give you a chance to begin afresh. For God’s sake do not go back to this wretched misery and in the old life but brave it for a new country if you possibly can. Don’t come back even for a day. You will break your heart if you do. I dare not put my name but we all wish you well.

God bless you.

I don’t know what became of Annette Williams after she entered the Female Preventative and Reformatory Institution on Euston Road the day she was discharged from prison in 1883. I don’t know if she travelled abroad, if she returned to her old life, or if she ever knew about this letter which was withheld from her whilst she was in prison. I know nothing about the man who felt compelled to write to her or what became of him. This letter offers far more questions than answers and has no real place in a more general history of female offenders.

However for all it lacks, the personal immediacy of the letter makes it powerful. I found myself wondering more about Annette and her life than I have for any offender in some time. I thought about her as a person with a story rather than a subject whose experience was to be reconciled as part of a sample of hundreds of others. Sat at my desk I was rooting for Annette. I found myself hoping that the rest of Annette’s life was a happy and successful one and fearing, like her anonymous letter writing friend, that if nothing changed it wouldn’t have been.