Mulling over the Muldoons

Even with the wealth of records at our finger tips for researching lives the dynamic between a women and men who were married, cohabiting, or even courting, is difficult to gage. For those that leave memoirs or are deemed important enough to have biographies written about them we may be lucky enough to get some small insight into their personal lives and the characters of those they loved. Female offenders are rarely so lucky. Researchers of ordinary (and extraordinary) men and women whose significance was not recorded for posterity find themselves in a difficult position. Personal relationships are a hugely important feature of the lives we study. Events, opportunities, and choices are all shaped by those around us – people in the past were no different. The stories of female offenders would not be complete without details of their families and loved ones. To an extent we are able to recapture family and friendship groups. Birth marriage and death records, the odd line in a newspaper report, or even matching conviction records might give us a little piece of information about the men with who female offenders made their lives. This can be recorded and even analysed. Questions like; were the majority of offenders married? How many ‘significant’ relationships might they have in their lives? Were their partners offenders? can all be quantified and analysed. Many intimate questions cannot. Good researchers do their best to draw conclusions only on the evidence they can gather and the ‘facts’ they can confirm. We are only human though. Just because we can’t substantiate ideas and about offenders personal lives, it doesn’t mean we don’t have them. Many researchers have theories about life events and people that they study which are considered in light of evidence very likely even if they can’t prove them. In subtle ways, maybe even without realising it, these ideas can colour how we tell the stories of our subjects. When new information comes to light, the smallest crumb of evidence can cause us to question some of the cases we are most familiar with. If you’ve followed my research, heard me talk, or come across the WaywardWomen site and twitter feed, no doubt the fearsome figure of Margaret Muldoon will be a little familiar. It was her story that first inspired me to blog the history of female offenders.

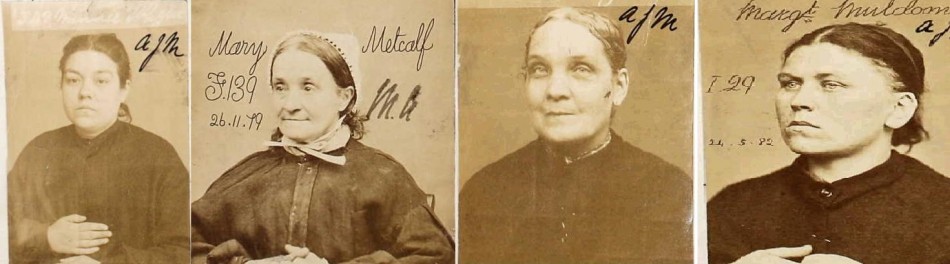

PCOM4; Piece: 59; Item: 6

The tale of the ‘Captain and leader of the rough women of Stockdale Street’ was the very first I uncovered, and Margaret’s story of hardship and loss, violence, persecution and redemption has continued to fascinate me. Her tale would not have been complete without the ominous figure of her husband, John, of whom I knew so little, lurking in the background. I knew almost nothing about John – only what the papers disclosed. He’d been sent to Prison just months after they married for an attack on a woman named Ann Hines. Margaret was pregnant with their first child and left to cope alone. Two years later she began her own five year sentence for an attack on the same woman. The pair did not correspond whilst in prison, not even in special circumstances when their son died. After they were both released in 1884 Margaret was never convicted again, seemingly turning her back on the violent life she had lived before. John did not. In 1891 was the victim of a violent attack which almost cost him his life when adversaries from his past caught up with him. He died a few years later at the age of just forty-five. With his death, Margaret was able to extricate herself from the dangerous and difficult community in which she and John had lived their whole lives.  Although I was careful never to treat it as evidence, over the course of my research, I’d made some assumptions about John Muldoon that encouraged me to view Margaret’s story in a certain light. I’d imagined him as a domineering presence in her life, a bad influence perhaps. The John Muldoon of newspaper reports was a violent and unsympathetic character. Then, just days ago, Find My Past published a huge collection of criminal records for British including the PCOM 3 Male Licences. For the first time I had the opportunity to fill in some of the last missing pieces of Margaret’s story – details about John The licences are not only a remarkable resource due to the in depth information they provide about offenders. They are also captivating in the sense that they allow researchers who deal in ‘criminal lives’ to come face to face with their subjects by looking at their mugshots. What I was unprepared for was that coming face to face with John would show me a man I never expected. John Muldoon was not the hulking brute that sources and my own imagination had led me to believe, but a rather diminutive man, just a few inches taller than his wife, who looked swamped by his prison uniform.

Although I was careful never to treat it as evidence, over the course of my research, I’d made some assumptions about John Muldoon that encouraged me to view Margaret’s story in a certain light. I’d imagined him as a domineering presence in her life, a bad influence perhaps. The John Muldoon of newspaper reports was a violent and unsympathetic character. Then, just days ago, Find My Past published a huge collection of criminal records for British including the PCOM 3 Male Licences. For the first time I had the opportunity to fill in some of the last missing pieces of Margaret’s story – details about John The licences are not only a remarkable resource due to the in depth information they provide about offenders. They are also captivating in the sense that they allow researchers who deal in ‘criminal lives’ to come face to face with their subjects by looking at their mugshots. What I was unprepared for was that coming face to face with John would show me a man I never expected. John Muldoon was not the hulking brute that sources and my own imagination had led me to believe, but a rather diminutive man, just a few inches taller than his wife, who looked swamped by his prison uniform.

PCOM3; Piece: 658

I was also surprised to see that he had fewer – by almost half – convictions for drunkenness and violence to people and property than his wife. Whereas Margaret’s most notable offence prior to her conviction for stabbing Ann Hines had been leading a rabble in an assault against the police, John’s had been to steal a newspaper at the age of thirteen. For that offence he was sentenced to ten days in an adult prison, and five years on the notorious Catholic reformatory ship, the Clarence. It was hard not to feel a little sympathy for a man who had been institutionalised as a child. What’s more, John claimed that he was wrongly convicted of the assault in 1880. This in itself was a normal petition for most convicts to make in a bid for freedom. There were few in convict prisons who openly admitted their guilt. What was more surprising was that John claimed he had been set up to take the fall for somebody else – Margaret’s sister. The validity of John’s claims are impossible to establish. However, his statements and a little more information on his history do provide a fascinating alternative perspective on the Muldoons. Was Margaret’s attack on Ann Hines motivated solely by revenge for her husband or was there a deeper more complex relationship between the two women now lost to history? Perhaps Margaret was not influenced by the violent world of her husband. If anything it would appear it may have been the other way round. Did John stop her leaving the area in later life, or had he been the one making it safe for her to stay? More records always mean more questions – but hold the promise of better and more thorough answers in the end.

Victorian gender norms made it common for newspaper reports and court testimony to paint male offenders as every inch the hardened and dangerous offenders that society held them to be. The sexual double standards of the nineteenth century suggested that if husband and wife were both embroiled in a world of vice and crime, the woman was immoral and weak, but the man was to blame. Criminal men were the seducers of women and the corrupters of their hapless female accessories. Often, with little evidence available to counteract these narratives old assumptions can seep through time and saturate, even unconsciously, our modern interpretation. In the rare cases where we have a chance to trace not only offenders but their partners – in life and in crime – it’s possible to challenge not only what contemporary witnesses and reporters said about them, but also the faulty picture we have formed in our own minds.