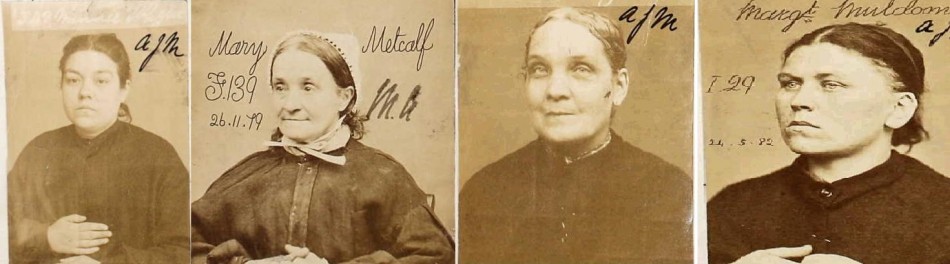

From the earliest representations of offenders right up to the politically and socially charged documentaries that ‘uncover’ crime and disorder in the present day (Ch4’s “Benefits Street” being a prime example) offenders have been cast in a particular role. Offending is not merely portrayed as an illegal act but, more often than not, a set of values and behaviours that individuals who transgress the law possess. Offenders are not just people that flaunt the law, but instead, they are ‘criminals’ – a distinct subset of persons who share a lack of morality and social conscious in common. Media representations of offenders might often focus on elements of a case that allows the perpetrator to be portrayed in way of this popular stereotype: Uncaring, morally bankrupt, dishonest, scheming, thoughtless. The nature of surviving accounts, both historical and contemporary , that we are offered of crime and offenders more often than not helps to proliferate and reinforce these ideas. But on the rare occasions when we are offered the chance to see circumstances and events from a different perspective, an altogether different picture is presented.

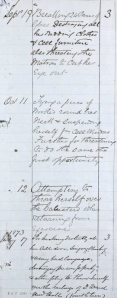

One of the biggest benefits using the proceedings of the Old Bailey give us is the ability to engage with testimony of offenders themselves. The trial reports allow us to hear individuals offer a defence in their own words, or a fierce rejection of the testimony given against them, or perhaps a candid answer to a question. Although far from perfect – the OB, for example, rarely allows us to see what questions were asked of offenders – accounts such as these are the closest historians are able to get to hearing our subjects speak. Their priorities, wants, needs, and negotiations all laid out for us on the page. Sometimes it is through these encounters that we are given unexpected glimpses into the social codes, sense of right and wrong, and relationships that shaped their world.

In February 1788 Martha Cutler, Sarah Cowden, and Sarah Storer were brought up in the Old Bailey on a charge of highway robbery. This crime was a most serious offence, not only for its distressing and violent nature, but also on account of its fearsome reputation.

Their victim, Henry Solomons, maintained that he had being going about his business in Whitechapel , in June that year, when he was accosted by three or four women at the end of an ally. Solomons testified that the women made use of obscene gestures and ‘very bad expressions’ and pushed him into a passage that led into a house. As Solomons was ushered into a small room and thrown down onto a bed, where with two women restraining him, a third took over fourteen guineas from his person. When the ordeal was over, he was let up and told to go about his business. Solomons and a number of other witnesses, including a policeman, were able to identify the three women on trial.

Despite all protesting their innocence and claiming police brutality all three women were found guilty. The sentence passed down to them was death.

Cutler, Cowden, and Storer were all returned to custody to await their fate. Over one year later, which the women would have passes in the cramped and unsanitary confines of the local gaol, they were bought back to court. Each woman was offered a pardon, granting her respite from the gallows on the condition that she submit to being transported to the new colonies in New South Wales – for the term of her natural life.

Such was their conviction that an injustice had occurred, all three women gave the same surprising answer – to choose death rather than to live on the other side of the world wrongly convicted.

Sarah Cowden replied:

‘No, I will die by the laws of my country; I am innocent, and so is Sarah Storer ; the people that had the money for which I was tried, are now at their liberty, therefore I will die by the laws of my country before ever I will go abroad for my life.’

Martha Cutler:

‘Before I will go abroad for my natural life, I will sooner die.’

And finally Sarah Storer:

‘I will not accept it; I am innocent.’

The women were again sent down. The irritated magistrate informed them that their lack of gratitude for the king’s mercy would result in immediate execution.

Yet, in June 1789, the women still sat imprisoned, awaiting the sentence. They were again bought up to the court. Once more the women were offered respite of the death sentence on the condition they be transported for life. Sensing her chances were running out Martha Cutler agreed to save her own life. Sarah Stoner attempted to bargain. She would agree to go, but not for the term of her whole life. The court decreed this offer to be an insult to their mercy, and no agreement was reached. Eventually Storer consented to life. Sarah Cowden also attempted to bargain. Most surprisingly, this was not for her own life – but her friends.

She stated:

“I will tell you what; I am willing to accept of whatever sentence the King passes upon me, but Sarah Storer is innocent, I would not care whatever sentence I went through; I will accept it if that woman’s sentence is mitigated.”

“I will take any sentence, if that woman’s sentence is mitigated.”

After another several exchanges with the court, where it was explained that she would either humbly accept the pardon or die, her resolve was as firm as ever.

“I will never accept of it without this woman’s sentence is mitigated.”

All the women were removed from the court except for Cowden, who spoke freely:

“Gentlemen, I hope you will excuse me for being so bold to speak in the court, but this woman is as innocent as a child unborn; she happened to come into the place where this robbery was done, she asked for the loan of a pair of bellows, and she was cast for death; and after being cast for death, I think to be cast for life is very hard; if this woman’s sentence is not mitigated I will freely die with her, I am but a young girl, I am but one and twenty years of age”

Further reports from the court indicate that all three women were eventually set to be transported, although they do not appear in the British Convict Transport Registers. One scholarly article suggests that Cowden later escaped the Lady Juliana convict vessel shortly before it sailed for New South Wales. She returned to London, and was discovered and brought back to the Old Bailey two years later, only to successfully win her freedom after pleading her belly.

This episode allows us to see Sarah Cowden not just as a serious property offender, but as a more three dimensional human being. By seeing her speak, we are offered a glimpse of a young woman with her own thoughts, motivation, and moral code. It would appear that Sarah Cowden was not devoid of feeling or sentiment, but instead a woman for whom the bonds of friendship and loyalty were worth risking life and limb for. A woman for whom, perhaps, justice and a sense of honour meant something. Even if we do not share the same understanding. Certainly I think we can discern that Sarah Cowden was, at the very least, a young woman brave enough to challenge authority in the courtroom and pursue her own agenda even though her status and gender both worked against her.

Instances when we can engage with female offenders exhibiting emotions and behaviours we ourselves might possess or recognise are, rather sadly, desperately rare. However when we are lucky enough to find them it is a vital reminder that not only could there be honour amongst thieves, but also decency, bravery, and friendship too.

Posted in

History and Crime,

London and tagged

death,

Offending,

Old Bailey,

Perception,

present day,

Records,

Stereotype,

Transportation,

Violence,

Women's History