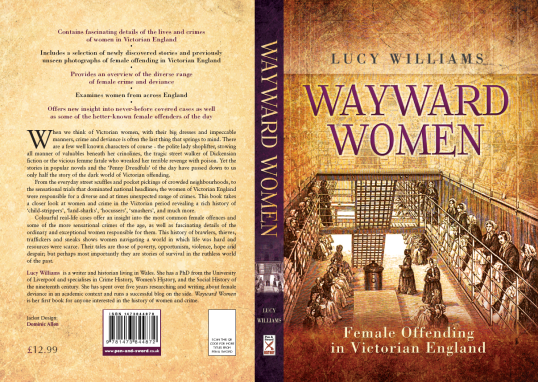

So much of the history of crime focusses upon the interaction between the legal apparatus of the state – the police, the court room, the prison- and the behaviours of those acting outside of social and legal norms. For historians and enthusiasts of crime history alike, it can be refreshing and rewarding in equal measure to take a brief diversion and consider some of the extra-legal methods used to control and counteract offenders and deviants.

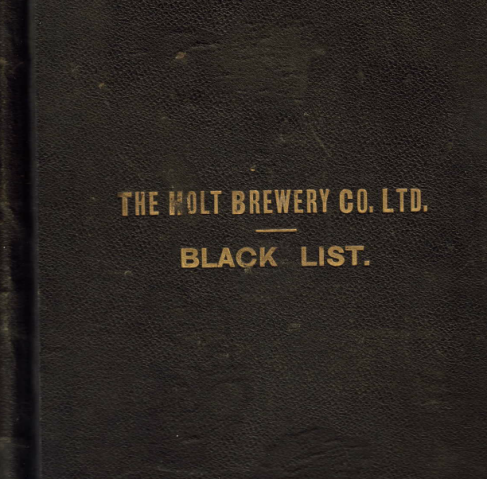

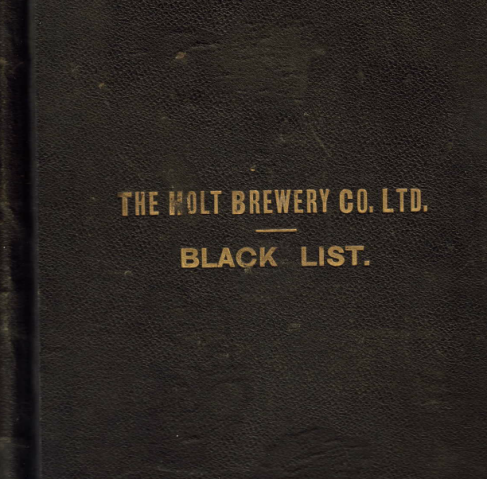

An intriguing collection recently released on the genealogy website ancestry.com The Holt Brewery Co. Ltd., Black List at the turn of the century shifts our focus briefly from the capital and ‘second city’ of Victorian England’s thriving empire, to another no less bustling but often historically neglected industrial hub of the country – Birmingham.

The 1902 amendment to the Licencing Act made it an offence for those identified as ‘habitual drunkards’ (those with three or more convictions for habitual drunkenness) to attempt to purchase, or to consume intoxicating liquids. At the same time, this legislation left licenced premises and individuals liable to prosecution if they served alcohol to such individuals. Documents like the Holt Brewery’s Black list were created by local committees with the help of local authorities to assist publicans and licensed individuals identify and refuse service to local habitual drunkards.

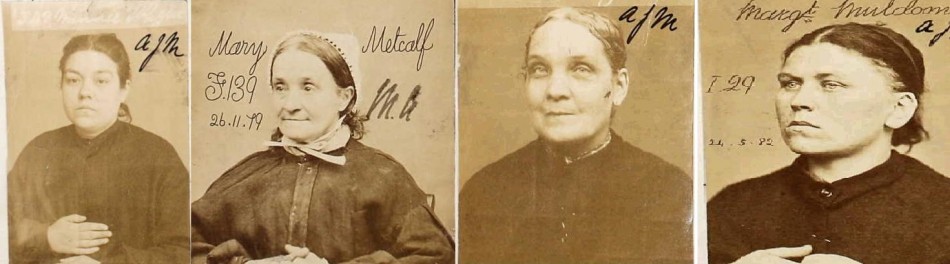

This particular issue, created around the turn of the century contained the records of eighty-three individuals. Despite the abundance of Victorian rhetoric about the values of the fairer sex, thirty seven of these individuals were women. There are a great number of uses for a source such as this, and the information contained within its pages offers a historian a number of avenues of inquiries. The first and most simple of these may at the same time be one of the most interesting. What type of women might find herself upon the pages of a Birmingham brewery’s little black book?

Contrary to what we might expect of Victorian habitual drunkards – all of the women save two were employed – alcohol abuse affecting not just the down and out, but an addiction that could plight the life of regular members of a community. The women worked predominantly as factory workers (metal polishers, press operators and the like) charwomen, but others worked as street sellers, dressmakers or laundresses. The women on the brewery’s blacklist are of course all working class – this is not to say that Birmingham was unique in having no middle-class or upper-class women that over-indulged in alcohol, but then, much as now, working class drunkenness took place in more public locations and spaces, than the middle-class equivalents who’s drunkenness took place more privately.

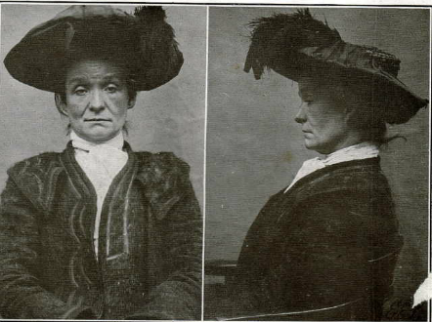

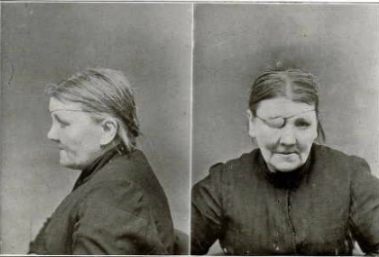

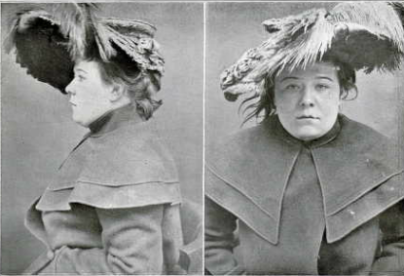

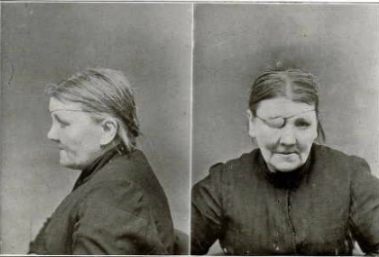

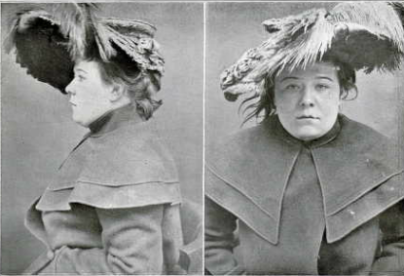

Eight of the habitual drunkards also worked as prostitutes. These were women who did not obtain their sole living through prostitution, but relied upon the trade as a strategy during times of financial hardship to supplement their earnings, or as Judith Walkowitz detailed, as a way obtaining money that allowed them to be more active consumers – or quite simply, to provide ‘spending money’, be that on alcohol, entertainments or fashion. Sarah Henson or Elizabeth Thompson (pictured below) may well have been such individuals.

Overwhelmingly, the women were in their thirties and forties, with only five offenders being over the age of fifty, and just two offenders being twenty-five or under. A real contrast to the modern day perception that it is youth drunkenness that blights towns and cities nation-wide. Given that the majority of women were of an age where we might expect them to have a stable domestic setup, it is perhaps surprising that eight of the women could give no place of abode, the reset inhabited either court dwellings, or lodging houses – where they would pay by the night to stay. Less than five of the women were listed as married.

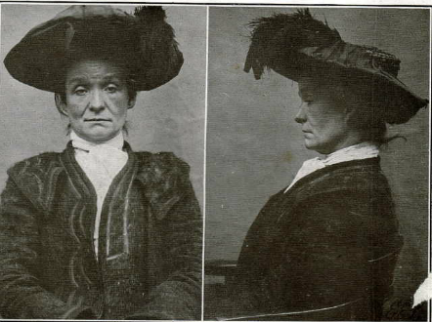

All but ten of the women were listed as having aliases, most used one or two, but a minority had four or five. This is significant only in the link that can be drawn between the use of aliases as a sign of not only repeat convictions, but also perhaps a wider criminal career than just drunkenness. Similarly to this, thirty-one of the women had scars or disfigurements –the most sever of which was Kate Kibble who had lost an eye, or a minority of offenders who had severe scaring or had lost fingers. In general the women had mild facial scarring such as cut marks on the forehead or cheeks, and several had scars from broken noses. Such a predominance of facial scarring amongst the women would suggest that most had been involved in several violent episodes, be this street fighting, or as the victim of attacks.

Only three of the women had tattoos – amongst them the youngest offenders. The most interesting of these was twenty-five year old Alice Tatlow who not only had the initials (of family members of previous paramours) on her hands, but also pictures which may have related to either specific experiences, or more likely gang membership – such as clasped hands, a star, and the Prince of Wales feathers.

However, some were quite ordinary, Like Forty-six year old Mary Bayliss or thirty-nine year old Susannah Booton – who had few scars, no tattoos, or disfigurements, who somewhere to live, and who worked as a charwomen. In fact, unless you got close enough to inspect many of the women in detail, as they went to work or passed in and out of their lodgings they were unremarkable and in many ways indistinguishable from their law abiding peers – That is until they tried to enter a pub, and that unfortunate page in the brewery’s blacklist reared its ugly head.