Julia Rigby was born at sea in 1829 and grew up in Lambeth, South London. Julia would next step foot on a boat twenty years after her birth when, once again, a new life would begin. Little is known about Julia’s early years. She was likely from a poor family, and while her mother, Ellen, and brothers, William, James, and Edward, are all listed as her next of kin on official records, there is no mention of Julia’s father. There is no record of Julia’s employment, only of the living she made by picking pockets, or stealing from shops. Julia was only a young woman when she pleaded guilty to stealing a watch from the person of Frederick Armytage at the Old Bailey in August of 1850.

Julia was seen by several people clinging to her victim before the robbery, asking if he wanted to buy her a drink (a common tactic of both prostitutes and thieves, looking for easy prey in the evenings). Although Julia was only twenty-one, she had reason to be fearful of facing a severe punishment at a trial, which would almost certainly go against her. There were other convictions known by the court against her. Cumulatively, Julia had served several years in prison. She spent ten days in prison for her first offence as a teenager after stealing gingham (fabric). Then she served fifteen months for stealing a watch and chain, another two years for stealing another watch, and three months with hard labour in Brixton prison in 1848 for the theft of twenty shillings’ worth of flannel. Prior to her latest offence, Julia had been convicted just months before, in March 1850, for receiving stolen goods, for which she served another three months.

Julia’s criminal career stretched back to her mid-teens and she had only been out of prison two months when indicted for the theft from Fred Armytage. To the court there would have been little doubt as to her ‘bad’ character, and she could probably have expected to be punished with the full force the law would allow. Julia chose not to go to trial and pleaded guilty to the offence. Saving the court the time and money of a trial in this way often meant an offender could expect a more favourable sentence. Julia may have been hoping for this. There is also evidence to suggest that she pleaded guilty in an attempt to save her lover, William, who was accused alongside her.

By pleading guilty and avoiding a trial, Julia took responsibility for the theft and was dealt with swiftly. She was sentenced to be transported for seven years. William Jones, with whom she lived ‘as man and wife’, had been with her that evening, likely picking out victims for her to target and receiving the stolen items when she was done. In court he denied all knowledge of the crime, and even association with Julia. He was found guilty in taking part in the robbery, but given just twelve months imprisonment for his role. The two would never see each other again.

Four months later, Julia sailed for Van Diemen’s Land aboard the Emma Eugenia. By the time she arrived in the colony in March 1851, her accomplice had less than six months of his sentence left to serve. On arrival in Australia, Julia claimed to be a housemaid, although this was unlikely to be true, due to her repeated spells in prison throughout her working-age life. She was five feet tall, fresh faced, with dark brown eyes, and a string of letters and numbers tattooed on her left forearm, commemorating the initials of loved ones, and her criminal history. The most recent were two characters ‘7 Y’ denoting the journey she had just begun.

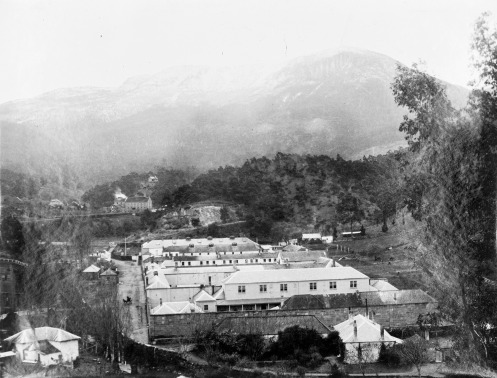

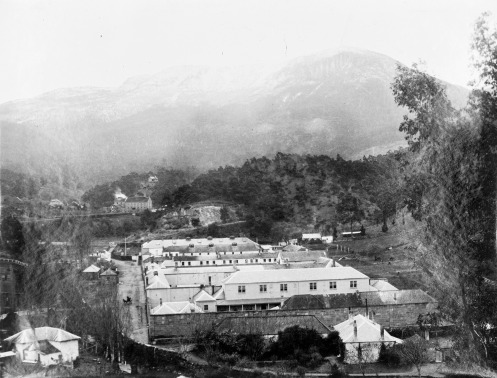

After bad behaviour throughout the journey, Julia was taken to Cascades Female Factory, where she spent three months under supervision. She was assigned labour in the summer of 1851, but returned to the factory to undertake three months of hard labour later that year for insolence. After being re-assigned following her punishment, Julia was relatively well behaved during her time in the convict system. She was returned to hard labour for a month on just one occasion, in 1852, after being found to have money concealed on her person.

Cascades Female Factory

While on work assignment, Julia met Joseph Lodge, a fellow convict, and the pair were granted permission to marry in 1853. Joseph, a Yorkshireman, had been transported to the colony in 1842 aboard the Marquis of Hastings for a term of fifteen years for murder. Joseph had a wife and children back in Yorkshire, whose fate at the time he married Julia is not known. Julia was granted her Ticket-of-Leave in 1854, three years before the expiration of her sentence. Her Conditional Pardon followed in 1856 (Joseph had received his in 1851). The pair went on to have seven children in the next fourteen years, and eventually settled on land they were granted in Tunbridge, roughly sixty miles each way between the major settlements of Hobart and Launceston.

Julia’s record read like that of a convict who would easily slip back into reoffending after the expiration of her sentence. She had a significant record of offending before transportation, had exhibited troublesome behaviour under sentence and had married a fellow convict, a murderer and a bigamist. Yet despite their criminal pasts, Julia and Joseph built good lives together. Tunbridge was a busy coaching town, providing accommodation and supplies for those travelling between two major settlements. The Lodges were a testament to the penal ideals of transportation; that by displacing convicts from their former lives, rather than just disciplining them and turning them loose at home, they were given the chance for a new start. An opportunity to build new, law-abiding lives.

It certainly seems that Julia and Joseph seized this chance. They were, by all accounts, respected members of their community. Joseph’s testimony on the drunk misconduct of a local police officer was key in his removal from post, Julia acted as witness in a case for theft, and Joseph was well known in the district as a fair employer and a reliable workman. They created lives simply out of reach of many British convicts rebuilding their lives on home soil.

Julia only ever came to the attention of the authorities again once, in 1870, when she visited an old friend from her convict days, Ann Reed, back in Hobart. Reed, like Julia, was now an innkeeper. After a couple of drinks together at Reed’s establishment, the Tasmania Arms, a fight took place between the two women in a dispute over money, which Julia said that Ann Reed and her husband had stolen. The case dragged on in court for over a week, with Reed prosecuting Julia for assault, and Julia bringing a counter-suit. The case was quickly and mysteriously settled when Reed agreed to pay Julia compensation to the sum of sixteen pounds. Julia returned to Tunbridge, her business, her family, and her law-abiding life.

Julia Rigby in later life

Julia lived the last years of her life in peace and obscurity. She died at the age of forty-seven at her inn in Tunbridge in 1878, after a short illness. She was respectably buried in Tunbridge and mourned by family and friends.

Julia’s life was a story of two halves, each beginning at sea. She had been a thief and pickpocket, a fallen woman living with a man outside the bonds of marriage, and would have undoubtedly been seen as part of the feared ‘criminal class’ at home in England. Julia would have seemed like a prime candidate for recidivism and a disorderly life in the colonies. Yet after her transportation Julia formed a family, became a property holder, a businesswoman, and pillar of her community. Julia’s penal, physical, and personal journey was remarkable, but not in its length or hardship nor particularly its impact on history. Her journey was remarkable because she travelled from poverty to prosperity, and from ruin to lasting respectability – much more than many of the girls raised in London’s slums could ever have expected.

You can read more about convicts like Julia and the journeys that took men, women, and children from the streets of Britain to the other side of the world in my new book Convicts in the Colonies.

Posted in

Australia,

Life Stories and tagged

Australia,

Book,

Convict,

family,

Marriage,

Respectability,

Social Mobility,

Theft,

Transportation,

Van Diemen's Land

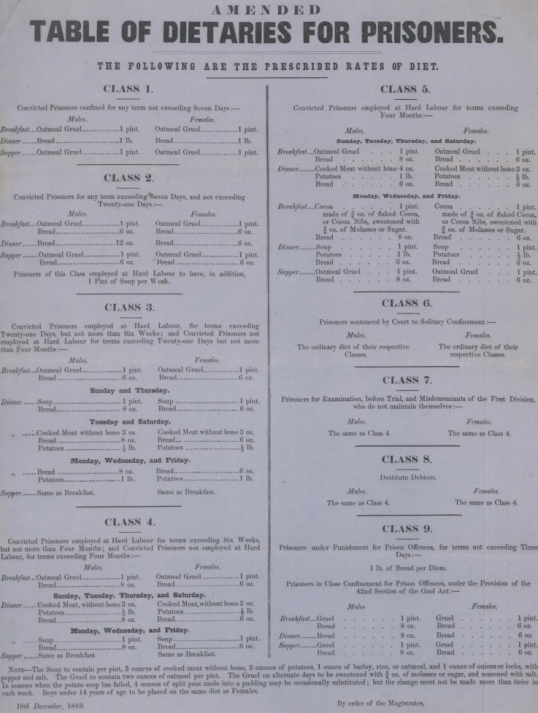

Example of prison dietary from Berwick Prison, 1849

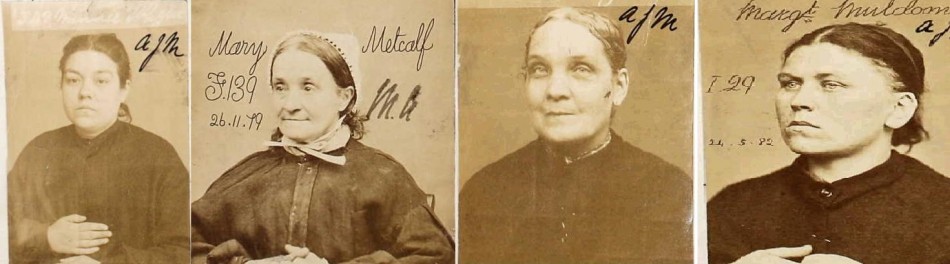

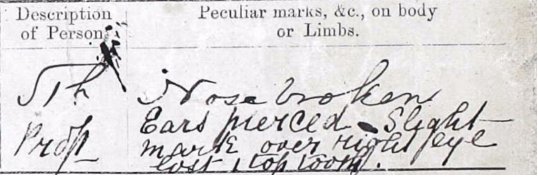

Example of prison dietary from Berwick Prison, 1849 Physical description of Mary Lynch, 1872. Text reads: ‘Nose Broken, Ears Pierced. Slight mark over right eye. Lost one top tooth.

Physical description of Mary Lynch, 1872. Text reads: ‘Nose Broken, Ears Pierced. Slight mark over right eye. Lost one top tooth.

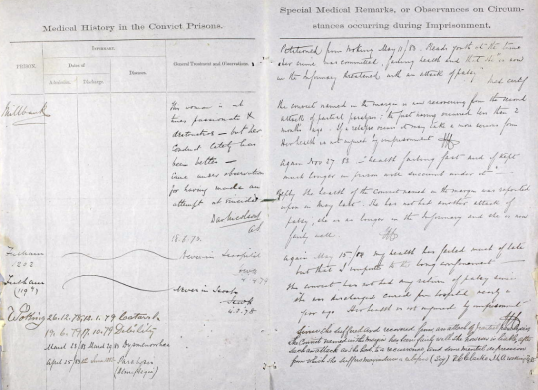

Record of prisoner complaints and medical officer’s evaluation and action.

Record of prisoner complaints and medical officer’s evaluation and action.