All Aboard the Amphitrite

Penal transportation to Australia is a fascinating subject for anyone interested in England’s history of crime and punishment. What we should make of transportation, and how we should perceive it as both a system of punishment and a human experience is something that divides historians. Few accounts of transportation to Australia would deny the horrors undergone by convicts who awaited transportation in hulks or prisons, or the terrifying and treacherous journeys facing those who sailed to Australia. When they arrived in Australia convicts could face back-breaking labour and a brutal system of secondary punishments which kept them under control.

However, some have also highlighted the benefits that transportation offered convicts. Prisoners under sentence could marry, they could take employment and earn money. Once a convict was issued their ‘ticket-of-leave’ they were essentially free to take advantage of the opportunities that the colony had to offer. They could find work, acquire land, and prosper. Freedom in Australia could bring a life *and climate* the likes of which many English convicts had never known. Digital Panopticon Ph.D student Emma Watkins recently spoke about the success of Mary Reiby, transported to New South Wales at the age of fourteen, who built a family and a successful business after the expiration of her seven year sentence. So remarkable was Mary’s contribution to the colony that since 1994 her face has graced the Australian $20 Bill.

Of course, not every convict story was as happy as Mary’s. It would only be too easy to view transportation through the rose-tinted lens of history, forgetting the immense psychological damage that could be done to those forcefully separated from everything and everyone they knew, transported across the world in bondage, never to return. Or the physical dangers that awaited those who sailed to Australia and toiled on its unfamiliar shores. Nonetheless, we have enough evidence to suggest that not all convicts looked to the colonies with terror. Some viewed the opportunities available to convicts in Australia as preferable to undergoing English punishment. Particularly in the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s when the horrors of initial settlement were largely over and two successful colonies in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s land were established. Some have even suggested that the end of penal transportation in 1868 was due, at least in part, to it no longer providing sufficient deterrent to convicts. Not all offenders were as opposed to life in Australia as we might expect.

Much of the history of transportation continues to interrogate these ideas. What was life really like for convicts in Australia? Who was selected for transportation and how? Did transportation offer a better prospect of reform, a better chance of offenders going on to have a ‘successful’ life? Did transportation work better than imprisonment? These are just some of the questions being considered by the Digital Panopticon’s Penal Outcomes theme.

In our haste to measure and chart the lives of convicts landing in Australia, we can often lose sight of the individual human journeys that were taking place. The great injustice befalling those sent unwillingly miles from home as property of the state, or the hopes and heartbreak of those who begged to go but never began a new life in Australia. Sometimes a single voyage, like that of the Amphitrite, gives us pause to think about the people behind the penal outcomes, and the multiple tragedies revealed by transportation.

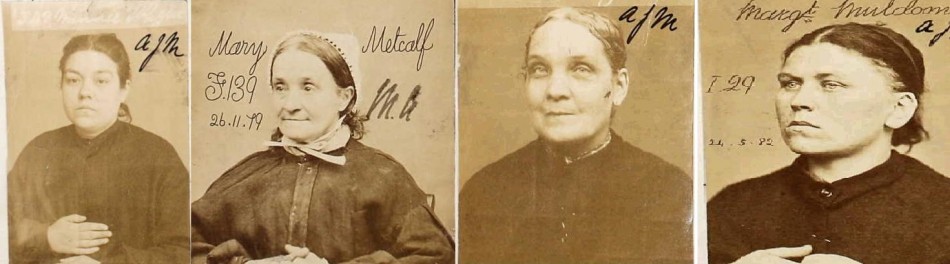

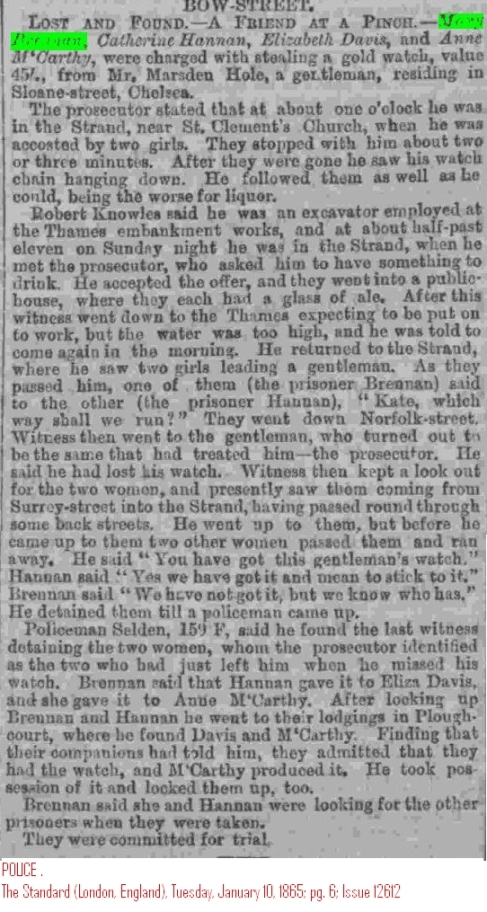

In late August 1833 the convict ship Amphitrite set out from Woolwich, bound for New South Wales. Officially on board were 101 female convicts (historical accounts also suggest that there were seven other convict women, and twelve of the convict’s children between the age of two and twelve). The female convicts came predominantly from London and Scotland although there were a scattering of women from other areas of the UK. Unlike many of their peers who could wait upwards of two years to board a convict ship, all of those on the Amphitrite had been tried in 1833 and waited just a few months before departure. The women aboard the Amphitrite were in many ways indistinguishable from the majority of other nineteenth century female convicts. All were between the ages of sixteen and forty. Those from Scotland were reportedly notorious recidivists, and from the details available of the women sentenced at London’s Old Bailey, a good proportion of them were prostitutes. Women like Mary Stuart and Charlotte Rogers convicted of picking their customer’s pockets and sentenced to fourteen years transportation. We know some by their own admission were guilty, and others like Mary Hamilton, sentenced to a term of fourteen years, may have been innocent. In Hamilton’s case even the victim of a robbery, Williams Carter, admitted ‘I cannot say the prisoner is the person’.

As a rule, female convicts on ships like the Amphitrite tend to leave very little in the way of evidence about how they felt about the sentences they were given. All we can do is imagine. Did women like Mary Brown, who ran a ‘house of ill fame’, and Charlotte Smith, a prostitute, who worked with her to rob a customer feel relief when their death sentences were commuted to life in Australia? Were the women terrified and devastated, or like Caroline Ellis, seemingly indifferent. Ellis was overheard by a policeman speaking to a fellow inmate at the local lockup, herself a returned transported, stating matter-of-factly that she supposed she ‘should be transported this time’.

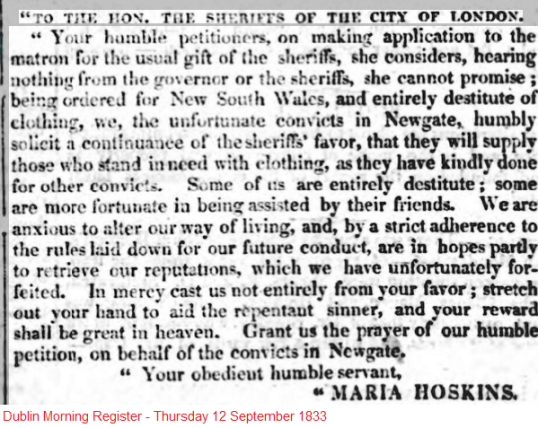

There were others like Maria Hoskins, aged twenty-eight, who admitted in court that she wanted to be sent to Australia. Hoskins stole a watch from her land lady and pawned it. The landlady discovered the theft and asked for the pawn ticket so she might retrieve the property. Hoskins replied, ‘No. I will not do that; I did it with the intention of being transported’ Hoskins refused to say were the watch was pledged until her landlady fetched a police officer to arrest her. She told the arresting officer, ‘If you have any compassion on a female you will take me up – if you do not, I will do murder.’ Hoskins, impoverished and desperate, saw the potential for a better life in Australia. Police constable Richard Broderick testified, ‘I took the prisoner; she said if she was not transported for this, she would commit something more heinous that would send her out of the country – that she had applied to Covent-garden parish for relief, and had been refused, and if she came across Mr. Farmer, she would drive a knife into him, and hang for him.

Hoskins was given the desired sentence – seven years transportation. Hoskins even appealed to the authorities that she and her fellow convicts be granted new clothes for their fresh start in Australia, in which she stated she was ‘anxious to alter her way of living.’

Tragically, like the other 100 known convicts on the Amphitrite, she never reached her destination.

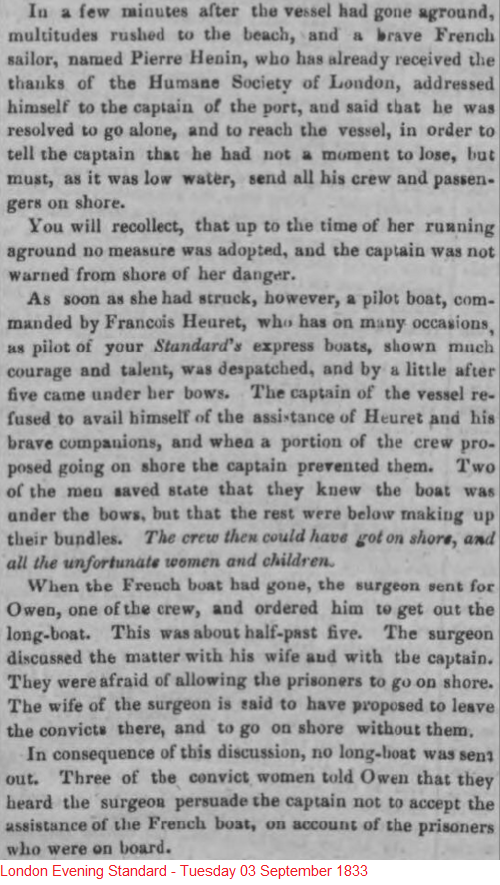

The Amphitrite was caught in a severe storm off the coast of France on August 31. The ship was completely destroyed, and every convict woman, every child, and all but three of the crew were drowned. The Amphitrite was the first convict vessel to be lost since the start of transportation to Australia, and the first loss of a female convict transport.

The tragedy of the Amphitrite became scandal when it was revealed by observers and the three survivors that the captain had refused help offered by those close by on shore because there were female convicts aboard. The captain considered releasing the crew and children and leaving the convict women to their fate, and ultimately refused the help of rescuers lest the convicts made a bid for freedom.

The Amphitrite, subject of ballads and paintings for the rest of the nineteenth century has largely disappeared from modern histories of transportation. As has the convict vessel Neva, carrying 150 Irish female convicts and thirty three of their children, which sank of the coast of Australia less than two years later. However, their stories are a microcosm of transportation through which we can think about the very human experience – and cost of punishment. What did transportation mean for female convicts and the lives they left behind? Was the prospect of a new beginning never entirely separated from the stain of conviction, or did the status of a convict follow some until their final moments? Voyages like the Amphitrite also remind us of the danger faced by convicts at every stage of the journey. As they waited in appalling conditions to sail, as they faced childbirth, disease, and rough seas, an as they worked through the convict system in Australia in the hope of freedom and a fresh start. There is something to learn from every voyage, every ship, and every convict –women like Mary Hoskins who was willing to go to extraordinary lengths in pursuit of a future that would never arrive.