The iconic opening line from L. P. Hartley’s 1953 novel, The Go Between, has come to encapsulate the way many of us think and feel about the past. Whether it is the ninth or the nineteenth century that we look to, the same temptation confronts us; to explain the past as a place intrinsically different from our own, and its people as individuals fundamentally different to ourselves.

Whilst these sentiments may hold true for some of the most visible elements of any age – technology or social customs – other elements of the past often provide a striking mirror in which to examine our own lives and societies.

The history of offending and offenders is one such mirror. In some ways, Victorian England’s female offenders did live in a foreign country. One where employment opportunities, living standards, and state intervention took a very different form to those of the twenty-first century world. However, should their social and personal lives be assumed so very alien to our own?

Perhaps the uncomfortable truth historians must acknowledge is that, in the course of their lives, many wayward women and their families met with the same situations, difficulties, and discrimination that a number of vulnerable individuals and groups face in Britain in the present day.

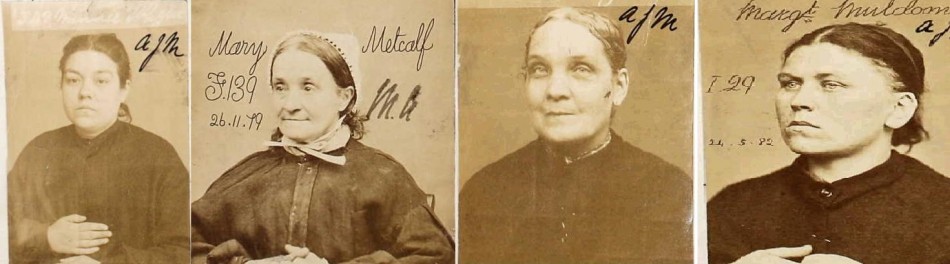

Mary Brennan’s life and slide into offending offers one such example.

Home Office and Prison Commission: Female Licences; Class: PCOM4; Piece: 61; Item: ;. Page: 40.

Mary Brennan was born in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire in 1850, the daughter of John and Jane Brennan. The Brennan’s were originally from Scotland, but moved around England during Mary’s early life, due to John’s work as a travelling acrobat.

The Brennans were a large but close family. Mary was one of the youngest, only she and her brother John junior remained at home by 1861. John Brennan made money enough for the family to be solvent without his wife Jane having to work, and for his children to attend school.

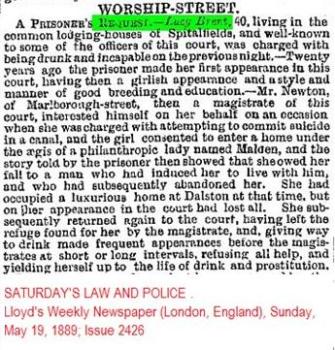

This happy and stable life was shattered in the early 1860s. The family had been lodging in Westminster, London, when John unexpectedly died. The Brennans lost a father, husband, and head of the family. Even more devastatingly, they had lost an economic lifeline. Employment for unskilled women in London was not abundant. Jane was only eligible for the lowest paying and most menial jobs, such as charring or laundering. On such a scant wage, in a period where the only state relief available was the workhouse, Jane was unable to sustain supporting her family. With some of Jane’s older children already moved on and married, and her oldest son off working as a travelling performer, the family unit crumbled. Fourteen year old Mary Brennan found herself cut adrift from her old way life. Like many young teens suddenly without an authority figure, Mary found herself immersed in a new way of existence, fraught with as much danger as there was opportunity.

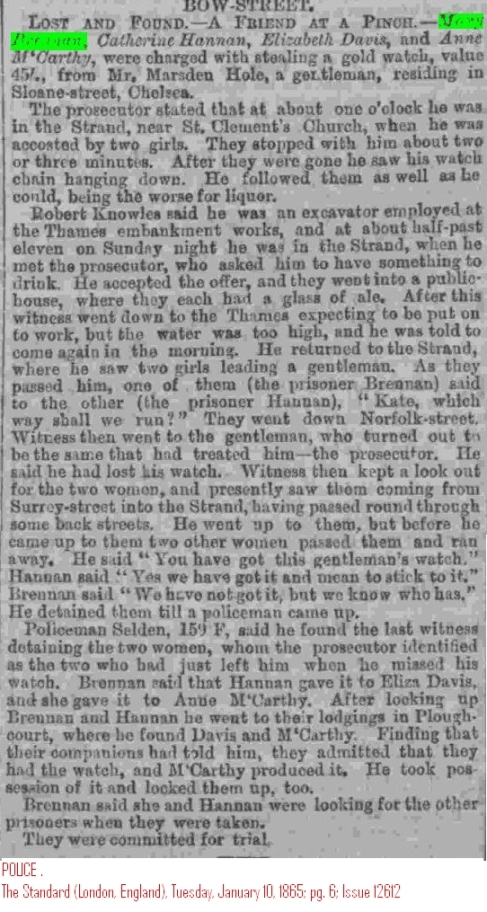

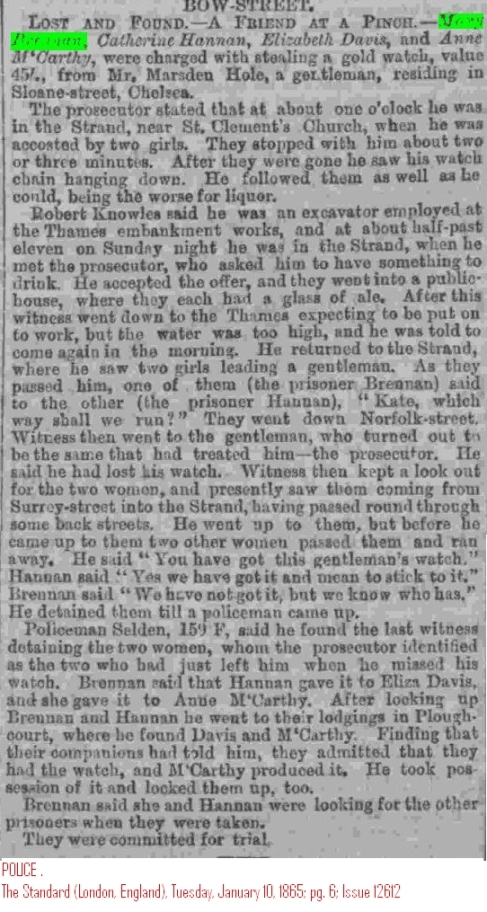

By the age of fifteen, perhaps out of economic necessity, perhaps out of camaraderie for her new peers – a group of three or four ‘street girls’ of a similar age and economic stance to Mary – or simply out of a need for attention; Mary had been arrested and sentenced to a year in prison for loitering on the street, drinking and picking pockets.

Without the money or personal connections needed to reinvent herself, Mary’s life course was irrevocably altered by the time of her release, aged just sixteen. After her months in prison, Mary did not return home to her mother, who was still living in London. Mary began cohabiting with a petty offender five years her senior – Francis Knight. No doubt the older and independent Francis seemed an attractive proposition to a young girl with nothing.

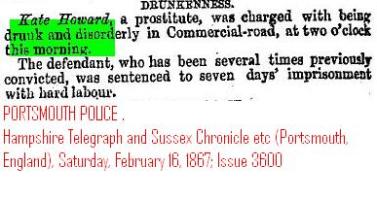

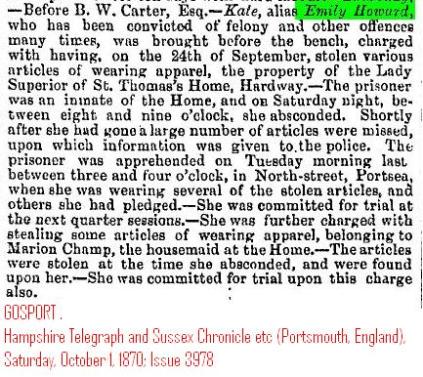

Mary and Francis never married, but by the age of eighteen Mary had given birth to two of his illegitimate children – Jane in 1867 and Francis in 1868. These developments further solidified Mary Brennans transition into a life of offending. In the few years she spent living with Francis Knight, Mary was frequently in the police courts, and in and out of prison several times for various street offences such as drinking, assault and theft. Mary had also gained the infamous label of prostitute.

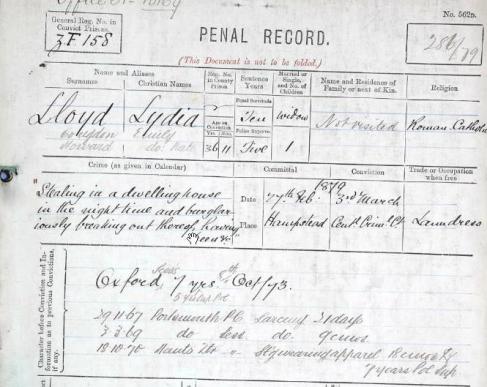

1869 was another turning point in Mary’s career of offending. By the age of nineteen she had become notorious with the police and magistrates, so when she was discovered stealing £10 in bank notes from a dwelling house in December that year, the court had no hesitation in handing down the maximum sentence for an ‘old’ offender. Seven years penal servitude.

Her relationship with Knight disintegrated during her sentence – imprisoned for seven years, she was no longer of any use to him. In the mid 1870s after her discharge from prison, Mary formed a new relationship with another offender, Thomas Lawrence.

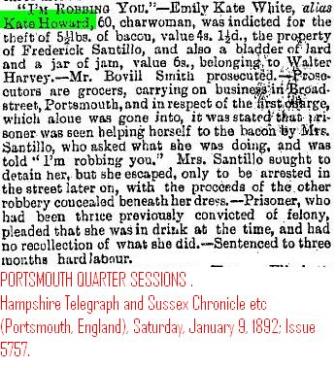

Mary Brennan had been living a transient life of repeat offending for longer than she had spent as a member of a stable working family in the time before her father’s death. It is perhaps unsurprising that Mary was thoroughly entrenched in her current mode of life, and that on each release from prison her life of vice resumed. In December 1881 Mary was again brought up at the Middlesex Sessions, charged with stealing £5 from the person, and sentenced to five more years penal servitude.

As Mary entered her late thirties and early forties, the cycle of offending, conviction, release and repetition resumed.

While some elements of Mary’s story are unique, and some of her difficulties and decisions were facilitated by social and cultural infrastructure that no longer exists, other aspects of her story highlight causes and contributions to a life of deviance and offending that are a product of the modern world; poverty, lack of early stage state support, and a punitive, ineffective, prison system.

The past is not a foreign country, but a neighbouring one. A place with which, it may be time to concede, we share a little too much socially, culturally, and politically. The people of the past still needed to eat and pay for housing, just as many struggle with today. Then, as now, people might find their lives spin out of control after life traumas such as bereavement and the disintegration of the family unit. Teenagers then, as now, still longed for independence, rebelled or were mislead by peers, often paying a high price for their transgressions. People in the past, just as now, were capable of making impulsive decisions – the consequences of which could last a life time.

When it comes to offending, perhaps it is most important to acknowledge that the lack of understanding and level of stigmatisation we see so clearly ruining lives in the past, continues to do so today.