Women’s work and ‘working girls’: Inspiration for International Women’s Day

Earlier today I was delighted to give a talk on the subject of ‘Inspirational women from Liverpool’ at the Museum of Liverpool in honour of International Women’s Day 2016.

Liverpool Is a city with a long history of inspirational women who have changed the lives of others and the world around them. With so much to choose from, the history of crime might not seem like the most obvious place to start a story of inspirational women in the city. However, its as good as any place for a day originally titled ‘international working women’s day’. A day which gives us an opportunity to celebrate the social, political, and economic contributions that women have made to the world -through hard work and perseverance.

We are used to thinking about women in the history of crime in two ways: of victims of crime – sexual and other violence in particular troubling women through history to the present day – or as victims of the legal process. The case of Florence Maybrick, has gone down in Liverpool’s history as a famed miscarriage of justice. We are also conditioned to think of women who break the law as villains. Not only on account of their criminal acts, but because so often breaking the law requires women to break gendered codes of expectation too. Criminal women can be so ‘unwomanly’. They harm children, can be lascivious or violent, or abandon their homes and duties for the pursuit financial gain. Liverpool’s Black Widows were immortalised in the popular press as inhuman, masculine, monsters. However, crime is not always black and white. There can be stories of success as well as despair. Light as well as darkness. Many suffragettes, who less than a century ago won the right of universal suffrage that we all now enjoy, were incarcerated as criminals . In history they are heroes, but in their day they were considered violent militants and disturbers of the peace.

One crime in particular has a long significance in the history of both women and Liverpool: prostitution. Prostitution is, as we might suppose, the battleground on which so many feminist and social issues have been fought. Consent, abuse, exploitation, and gender inequality to name but a few. Yet prostitution can also be a prism through which we can view the struggles, triumphs, and extraordinary stories of ordinary women. Prostitution can even be a place, somewhat surprisingly, where inspiration can be found.

From the mid-nineteenth century onward, Liverpool was not only a flourishing site of world trade, it was also a desperate place where many working class women struggled to survive. It was a city in which prostitution thrived.

Researcher David Beckingham estimated that ‘on the basis of criminal statistics, Liverpool was by some distance the capital of prostitution in Victorian England’. It also had one of the highest prosecution rates for prostitution in the UK, outstripping cities like London, Manchester, Birmingham, and Newcastle many times the size.

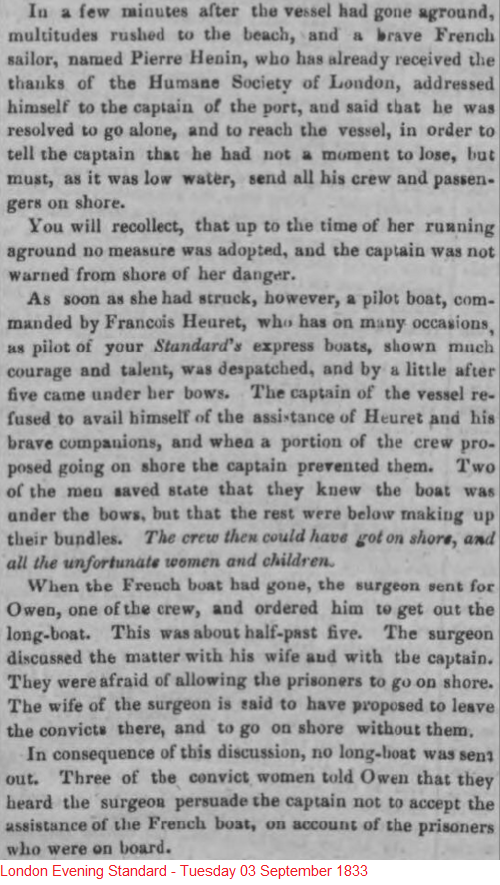

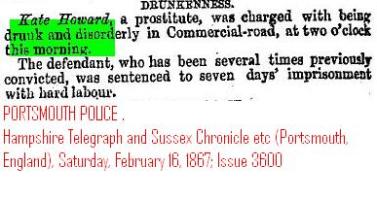

Life as a prostitute in Victorian England was a hard and unenviable one. By the 1860s life for prostitutes became even harder as the government moved to legislate against those working the streets with the Contagious Diseases Acts.

The first Contagious Diseases Act (CDA) was passed in 1864, and the acts were amended and expanded again in 1866 and 1869. They made provision for the apprehension, detention, and forceful medical examination of any woman suspected of being a common prostitute and suspected of having venereal disease in the port and garrison towns of England and Ireland. These acts gave the police the power to apprehend women they suspected of working as ‘common prostitutes’ and to take them before a magistrate who could order them to be detained in a lock hospital for invasive internal examination. If found to have a ‘contagious disease’ to be detailed for a course of mandatory treatment – up to six months long, before releasing them with a certificate of clean health. Women could be further required to report for fortnightly check-ups. If a woman refused to cooperate at any stage she could be convicted of an offence and imprisoned. If a brothel was found to be employing infected women they could be fined up to £20. The legislation gave already vulnerable women little place to hide.

The Acts were an unmitigated failure. Not only do we know that the horrendous and invasive treatments they forced on women had little medical affect, they also ignored the obvious reality that the spread of infection could not be stopped by only treating half of the sexually active population.

What these acts did achieve was to breach what we would now consider basic human rights – such as that to liberty and the right for women to control their own bodies.The CDAs persecuted and discriminated against women. Laying the blame for the sex trade and all of its perceived evils at the feet of the women who worked in the trade.

Josephine Butler moved to Liverpool in 1866, just as the acts were being amended – so that her husband could take up the post of principal of Liverpool College.

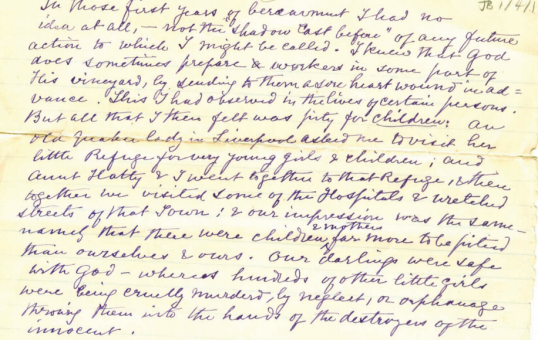

She had been raised in rural Northumberland, a world away from the wretched streets and Brothels of Liverpool. Yet almost immediately upon arrival in the city she began work with women and young girls who she met in the course of visiting the streets, hospitals, and workhouses of the city. Butler wrote to her Son that she felt compelled to help those who were so much less fortunate than herself.

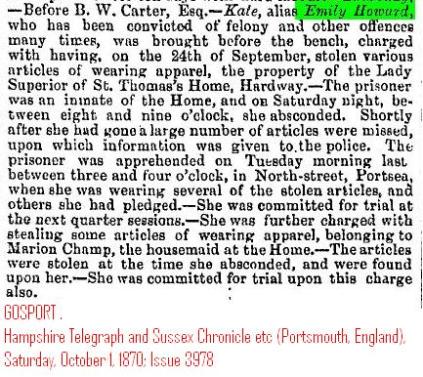

Her work began almost immediately, turning her own home into a house for dying women rescued from the streets and workhouses. Later, she rented premises near her home to run as a house of rest and industrial home. Butler’s institution was the first of its kind in the city. The home offered care for women who had once walked the streets and aimed to combat what she saw as some of the primary causes of women’s ruination. The poor level of education, training, and employment available to them in the city that saw the poorest and most vulnerable with little other option for survival than to sell themselves. Her industrial home took women from the street and gave them a small income in return for learning ‘honest occupations’ that might help them to live a ‘sin-free’ life in the future.

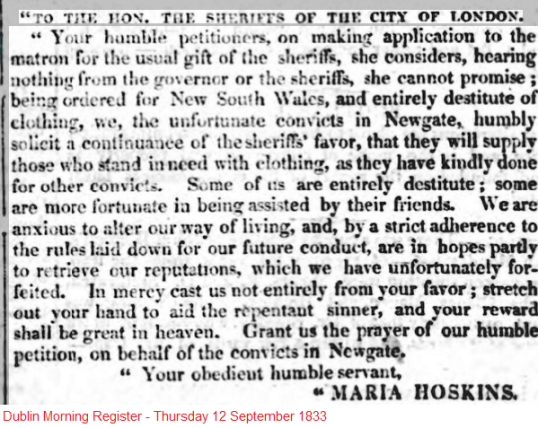

By 1869 when the final and largest extension of the contagious diseased acts were passed into law, Butler began writing powerful public papers rallying against the hypocricy of the acts, and the double standard which saw male promiscuity as natural, and female sexuality as a perversion, yet one that should be exploited ‘to serve the requirements of men’. She wrote of the acts, ‘their system is to obtain prostitution plus slavery for women and vice minus disease for men. In her paper the Moral Reclamability of Prostitutes she wrote that the acts rendered women ‘no longer women but only bits of numbers, inspected, and ticketed human flesh, flung by government into public market’.

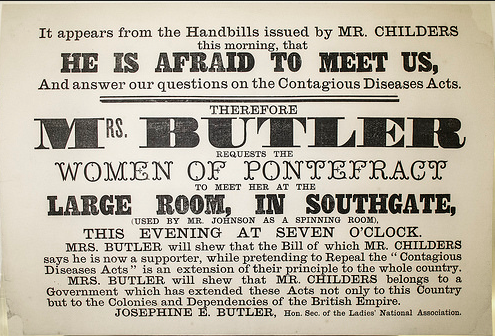

She founded the Ladies Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts in 1869, and campaigned through writings, speeches, and public tours for the next decade – despite battling with severe exhaustion. The association fought against the established acts on an eight point premise, and also fought against a counter-campaign which aimed to extend the acts throughout Britain.

The acts were repealed in 1886. But by 1882, when Josephine and her family left Liverpool she had written over forty books, pamphlets and speeches for the cause. She made a huge contribution to the campaign for the acts to be repealed, and doubtlessly impacted for the better the quality of life of women working the streets in Liverpool and elsewhere.

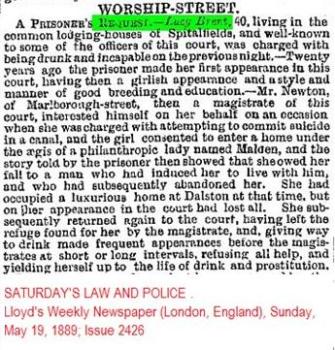

Unfortunately, only too often , International Women’s day is a time when we celebrate just the achievements of the great and the good. The Butlers, the Pankhursts, the Nightingales of the world. When it comes to prostitutes – still one of the most vulnerable groups of women anywhere – history remembers the men and women who advocated on their behalf but forgets the ordinary women who overcame appalling and extraordinary circumstances just to survive.

Minnie Wright was a contemporary of Josephine Butler’s but only in the very loosest sense of the term. Her life could not have been more different from Josephine’s, yet both women found their lives shaped by Liverpool’s sex trade during the period of the Contagious Diseases Acts.

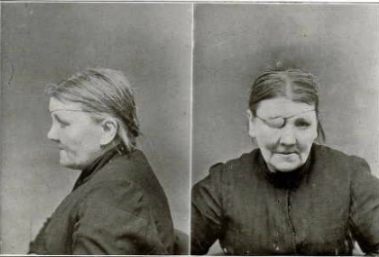

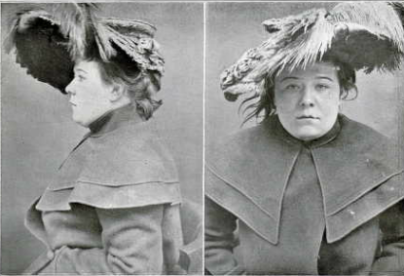

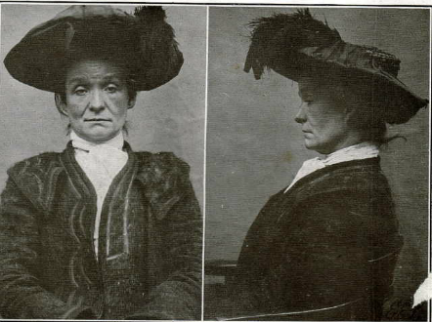

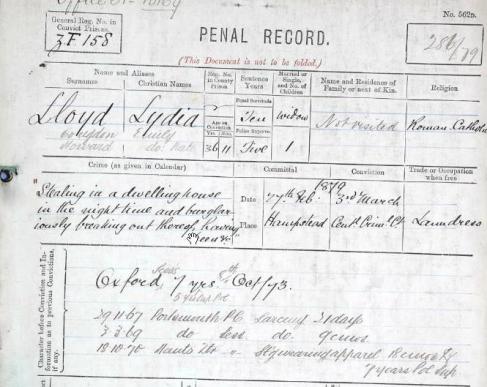

Minnie was born in Swansea prison in 1851 where her mother maria, a prostitute and thief was serving a six month sentence for theft. Minnie’s mother was a twenty-six year old famine migrant from cork, and her father was a fifty seven year old thief, abusive drunk, and pimp with a criminal record stretching back to before Minnie, her mother, and Josephine Butler were even born. Minnie grew up in a home where sexual and other violence by her father against her mother and others was common. By the age of six she was living with her family in a brothel in Liverpool. It is hard to fully comprehend what life was like for Minnie, living side by side with sexual exploitation and violence on a daily basis. She was married at sixteen but continued living at the brothel even as her children were born. Minnie gave birth to ten children, although only her son John and daughter Mary Ann survived into adulthood. In her early twenties, after the incarceration of both of her parents for running a house of ill-fame and death of her father, Minnie was left to run the brothel – her home and only source of income – alone.

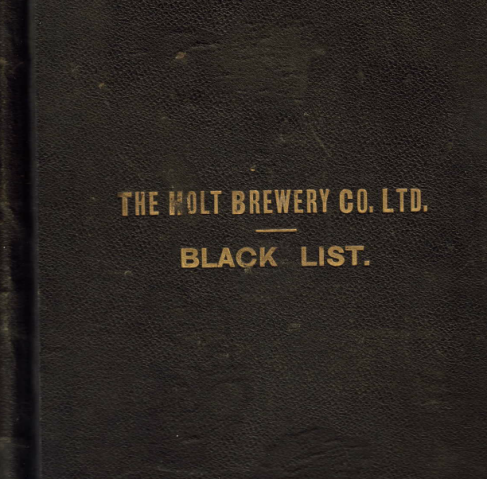

As the ladies Association were campaigning to repeal the CDAs in 1873, and the zealous policing of prostitution and brothels in the city was at its height, Minnie too was arrested and imprisoned for running a disorderly house. In the years that followed more prosecutions came as a string of new criminal activities – illegal drinking, gambling, and fencing of stolen goods – took place at the brothel. While Minnie must be viewed as responsible for the exploitation which occurred at the brothel, it must be acknowledged too that her options to make any other living were extremely limited.

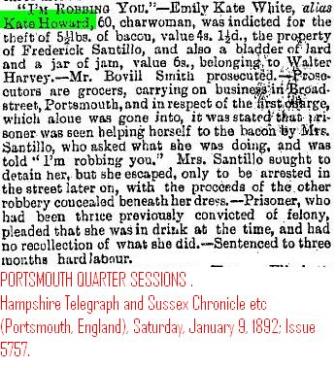

Minnie was the daughter of a prostitute, and a pimp. She had grown up witnessing in all its detail and horror the Victorian sex trade. Minnie lived in Liverpool’s notorious red-light district in which brothels and prostitution must have been normalised for many local inhabitants. She had no education, no training, and no prospect (with her reputation and background ) of obtaining any but the most poorly paying and casual work in the city. Work outside the brothel for Minnie, if not prostitution, would have involved street selling (hawking) or charring. During this period street work for women in Liverpool came with its own drawbacks and dangers.

A Map of Liverpool’s ‘Little Hell where Minnie and her family lived. The red lines illustrate locations of one or more known brothels 1860-1880.

A Map of Liverpool’s ‘Little Hell where Minnie and her family lived. The red lines illustrate locations of one or more known brothels 1860-1880.

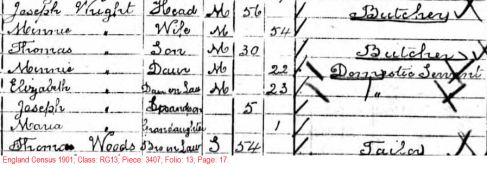

The year after Josephine Butler left Liverpool, Minnie was convicted of receiving stolen goods from her twelve year old son. Minnie was sentenced to five years in one of London’s convict prisons, and John spent five years in a reformatory. Minnie was released from Prison in 1886 – the year that the CDAs were finally repealed. Something – very possibly the long separation from her family – had changed for Minnie. Despite the considerable social barriers in her way Minnie changed her life dramatically. She took the money she had earned from her years at the brothel and moved with her family to the Wirral. there they began a legitimate business – a butchers. Run by Joseph, and joined, when he was released from the reformatory, by John. Minnie even managed to secure her daughter Mary Ann a domestic service position. While this might seem perfectly ordinary, for Mary Ann it was remarkable not only because she was born in a brothel, but also because her mother, uncle, and grandparents had all spent time in prison for offences related to prostitution or violence.

Given the overwhelming odds against it, it really is extraordinary that both of Minnie’s children lived stable , law abiding lives. Especially that her daughter, and her granddaughters, and great-granddaughters all lived respectable, law abiding lives – untouched by the misery of sexual exploitation into which three successive generation of women in Minnie’s family had been born. Minnie died at the age of eighty-eight. She had not changed the world, but in the face of real adversity – of personal tragedy and social restriction- she transformed her own life and the fortunes and opportunities of the women around her.

When we think of how women from the past might inspire us, there is room to draw from the small as well as the great, the pioneers who fought for all women, and even the ones that had only the means to fight for themselves.

Josephine Butler and Minnie Wright never met one another. They were women of vastly different family backgrounds, educational levels and social classes. Yet the lived in the very same city and their lives were connected by the injustice and sexual inequality of prostitution in Victorian Liverpool. Both women, through this unique moment in history, have something to teach us about women’s abilities and agency to shape their own lives, and the wider world.

Josephine Butler’s story is well known. She turned privilege and position into a opportunity to advocate against the injustices suffered by women with little social or political power to do so themselves. By contributing to the repeal of laws which persecuted and discriminated against women, Butler will have changed the quality, and probably the course of many lives. Minnie Wright’s life is not the stuff of history books, and rarely the stuff of talks, she had, you might think, little impact on the wider social and political lot of women in Liverpool. Yet should we consider her struggle any less difficult, and the repercussions any less monuments? Successive generations of the Wright family, Mary Ann’s children, and her children’s children lived ordinary lives, which is rather extraordinary when you think of what could have come to be. It is not just the great and the good like Josephine Butler, but the ordinary and every day women of Liverpool who have struggled against injustice, fought for every opportunity, and made the choices, that have changed the lives of women in the city, and in many instances their relationship with crime too.

Happy International Women’s Day.