Crime at Christmas.

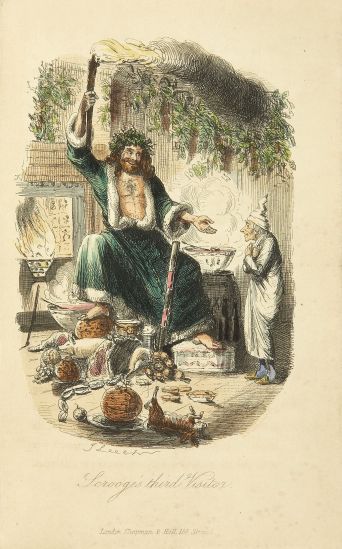

Christmas is a time of year that feels inescapably Victorian. Some of our most loved traditions and most familiar images of the festive season were made during this time. From prince Albert’s pioneering of the decorated Christmas tree, classic music such as ‘In the Bleak Midwinter’ or ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’, to our favourite stories such as Charles Dickens’ unforgettable A Christmas Carol. Although modern Christmas has had many welcome modern additions, at its heart, it’s still inescapably Victorian. One Victorian staple, however, is often far from our thoughts when we envision that crackling log fire, the stockings hanging on the mantelpiece, and the pulling crackers and a eating of a festive feast: Crime.

Twenty-eight year old Rebecca Porter began working as a domestic servant for a Mr and Mrs Harris in July 1864. Mrs Harris began to suspect that Rebecca was pregnant in October that year because she wore such a large crinoline (structured petticoat) to try and disguise her changing figure. Rebecca refused not to wear her crinoline, stating she would rather leave employment than to do so. On Christmas day Rebecca refused to join the other servants of the house in for morning chores due to what she called a ‘billious attack’. Rebecca was, in truth, giving birth to her illegitimate son, alone in her room. Immediately after delivering her child, Rebecca went downstairs to eat Christmas dinner with her fellow servants ‘in a desperate endeavour to avert suspicion’. Unfortunately, a court herd from witnesses, her agony was only too evident and the truth was discovered.

Rebecca had strangled her son almost immediately after birth but then attempted to wash her child, and wrapped it in cloth placing it in one of her storage boxes. Rebecca begged her mistress to be allowed to bury her child and to return to work for Mr and Mrs Harris but, unsurprisingly, Mrs Harris refused and sent instead for the police. Rebecca underwent two trials at the Old Bailey. One for murder, and the other for concealing a birth (a common lesser charge, often favoured for cases of infanticide). However, despite significant evidence to suggest Rebecca had purposely concealed her pregnancy, that she had made no provisions for the child’s life intending for some time to kill it, and the very obvious evidence of the injury to her son, she was found not guilty, and set free from court.

An almost identical case was brought against Martha Rogers, who on Christmas-eve. Martha 1850 left her employer’s house in Surrey, looking ‘very unwell’. She took with her nothing but a box and a few other personal effects. The box contained the body of her deceased illegitimate child that she had given birth to in secret in her master’s home. Martha then attempted to dispose of the child’s body by mailing the box to an unknown address. The package was traced back to her, but at trial, she, like Rebecca, was also acquitted of murder.

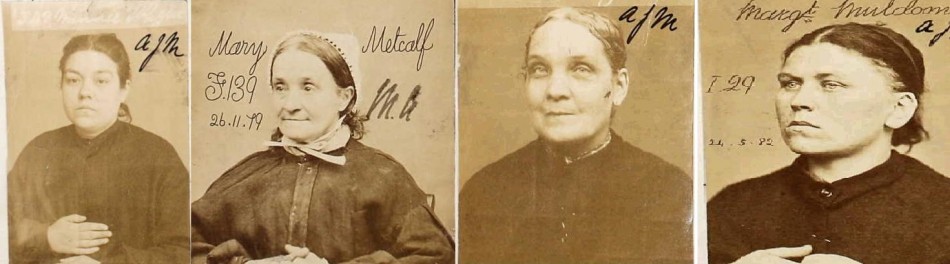

These Christmases, and these crimes, were not exceptional. Every Christmas in the decades both before and after, women up and down the country found themselves at odds with the law. Women driven to violence and murder. Those who used the opportunity of festive cheer to con their way into houses and shops so they might steal, and those who over indulged in festive frivolities and found themselves arrested as drunkards or a public nuisance. Ordinary women like Sarah Kelly, arrested in 1889 as a drunk, whilst sitting out on a step in Holloway on Christmas day, with her young children sat crying beside her. Or like Frances Gallimore, Agnes Martien, and Mary Lilly, all separately charged on Christmas day 1879 with running disorderly houses – brothels and lodging houses in which scores of women spent Christmas working as prostitutes.

The crimes committed by female offenders throughout the festive season, and even on Christmas day itself, were no more remarkable than any other time of year. Christmas crime was not special or particularly significant. But viewed through the warm and sparkling lens of our own celebrations, crime at Christmas often makes us dwell, more than any other time of year, on the causes and circumstances of offending which saw some have the worst time of their lives, even at the ‘most wonderful time of the year’.