Madge and the Many Magistrates

Margaret Lamb was born in Lancashire in 1896. Her Parents were Margaret and Edward Lamb, her father worked as a canal boatman. Margaret was the oldest of the Lamb’s five surviving children. In early life, Margaret was, in many respects, indistinguishable from the thousands of young women who lived in the still rural but ever industrialising north of England. Girls who would grow up to be a new generation of Lancashire factory workers, domestic servants, and farmer’s wives. By the time she was fifteen, in 1911, Margaret had left home. As was expected of many young women like her, Margaret had found work as a domestic servant near Bolton, allowing her to contribute the family coffers.

But the seemingly uninspiring circumstances of her birth and early life, even the meek and gentle image conjured by her very name, could not have been less fitting for Margaret Lamb, a woman who would become notorious in courts and newspapers half a world away as ‘Madge Foster’.

As the First world War approached, Margaret, like many young women in the early twentieth century, left England in search of a better life. Margaret travelled to Australia. Lured perhaps by better prospects for work, or better prospects for marriage she eventually settling in Peth, the remote capital of the country’s western state where successive gold rushes in the late nineteenth century had left the area prosperous, and where men outnumbered women by some way. In 1916, she was married to Arthur Gorge Lamb, and became known by the Australian abbreviation of her name – Madge.

A lack of census and other civil records for Australia make it difficult to ascertain much about the foster’s marriage, but with no records to indicate the contrary, Madge and Arthur seem to have spent a relatively untroubled decade as man and wife. It was in 1927, after more than ten years of marriage, when Madge was thirty years old, that she first came to the attention of the courts.

In time, Madge became known as a habitual and prolific public order offender, but the seeds of her offending career grew slowly. Her first offences in 1927, 1928 and 1929, were for minor infractions, disorder and the use of obscene language in public. Whilst it is entirely possible that Madge’s marriage had already broken down, and that her problematic relationship with alcohol was well ingrained, the activities for which she was prosecuted in isolation indicate little – other than a momentary loss of decorum, or an incidence of over indulgence. Transgressions which were met with a rebuke from the courts and a small fine. However, by the early 1930s, Madge was becoming a more frequent visitor to court, and her offences began to include drunkenness, pubic disturbances, criminal damage, and assault, an she experienced her first custodial sentences.

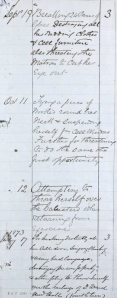

A small section of Madge foster’s entry in a local prisoners register

On one such occasion in August 1931, Madge was sentenced to a month in prison for drunkenly fighting with another woman, Ray Munro, after Munro supposedly insulted her by calling her a ‘woman police man’. Just a few months later, Madge was knocked down by a car in Perth, taken to the local hospital, and subsequently arrested for being drunk. So began a cycle of almost monthly arrests, incarcerations, or fines which would last years. Although Madge’s offences were primarily against public order, as work and money became harder to come by, she occasionally turned to theft, which could entail spending several months at a time in prison.

A ward of Fremantle Prison (WA), where Madge spent many terms of imprisonment

As her list of convictions, and the time she spent in prison, grew, Madge’s network of respectable friends and acquaintances, and her social safety net drifted away. Life became both more precarious and more dangerous as Madge spent increasing amounts of time on the street, at the mercy of the elements and neglected by society.

In 1935, Madge had been drinking in a hotel in East Perth when a row erupted between her and a group of men over a pot of beer. Later that evening, as Madge left the hotel, she was set upon by the group, and subject to attempted rape by several of the men – a crime only prevented when the hotel owner alerted a nearby constable. Madge was badly beaten and shaken. Only one of the men responsible, Edward Tester, identified as the ringleader, was taken to court. The charge of attempted rape could carry a sentence of up to 14 years imprisonment. The presiding judge, stated that Edward’s actions had been ‘attended by circumstances of very grave aggravation’ (namely that Madge had been requesting beer from the group in the evening) but that the attack made on the attending constable could not be borne, and sentenced him to four years imprisonment. None of the other men involved in the attack were ever apprehended, and Madge received no emotional support, help towards stable housing, or intervention for her alcoholism. After recovering physically from the assault, Madge’s cycle of offending resumed in Ernest.

Within months of Edward Tester’s conviction, Madge herself was imprisoned for an assault on a tram conductor in Perth. With several years of court appearances under her belt, Madge was becoming became more vocal in her defences and protests in court, quarrelling with police officers, insulting magistrates, and complaining about the criminal justice system which in her view, set people up to fail. She noted, in her first conviction of 1932 ‘If you send people to gaol, you are only making criminals of them’.

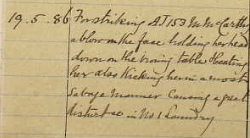

The Southern Districts Advocate, March 16th 1936

On another occasion a few years later, a magistrate tried to explain Madge’s offending by suggesting that she was too drunk to know what she was doing. Madge, who had not denied the charge of theft but vehemently denied being drunk simply replied ‘possibly, but not probably’ before she was sentenced to another month in prison.

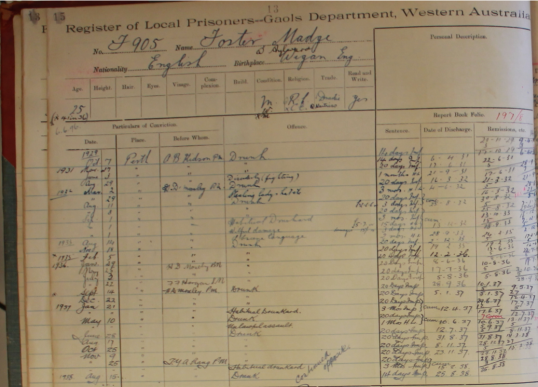

The Daily News, October 26th 1939

By 1940, Madge began to drift around the colony, wandering to Geraldton, more than 250 miles from Perth. Even at such a distance, her record was well known and within three days of her arrival, she was brought before the local magistrate and warned that if she did not quit the town she wold be imprisoned as a vagrant. Madge failed to heed this warning, and less than a fortnight later was prosecuted for being idle and disorderly, and for having no visible means of support. She was sent to prison for four months.

After her release, she headed back to Perth, and was soon back in prison there for drunkenness and disorder. Her frustration with the system evidently grew alongside her list of convictions. In April of 1942, when Madge was brought up in the Perth police court charged with drunkenness, a magistrate asked her the traditional ‘how to you plead’ to which Madge replied ‘I plead for mercy’. A lengthy debate then ensued between Madge and the magistrate about whether she had been drunk. In sentencing her to twenty days, he cautioned her, with no sense of irony, ‘If you continue like this, you’ll finish a habitual drunkard’. ‘That’ll be too bad’ was all Madge replied as she was led from the dock.

By the later 1940s, there was real evidence that Madge was trying her best to turn herself around. Although she spent Christmas of 1946 in prison, and the day after her release was given another 14 days in the new year of 1947, in the following two years she received just one conviction, and was not in court at all between November 1847 and January 1949. In recognition of her good efforts, when she appeared for drunkenness, early in 1949, she was released with just a caution. However, the rate of her convictions soon began to pick up again, with four more that year, three in 1950, and four in 1951.

The Mirror, January 4th 1947

Her appearances in court came to an abrupt halt in January of 1952, when she was hit, for the second time in her life, by a car in Perth and admitted to hospital. Although she recovered from her injuries, Madge would not trouble the magistrates of Western Australia again. In December that year, Madge’s relatively short and troubled life came to an end when she threw herself in front of a train in Perth. The driver of the train testified at the coroner’s court ‘he had seen a white hared woman leap high into the air from the platform and fall crumpled up between the rails. She seemed to straighten her body as the engine came closer but made no attempt to save herself’.

During her lifetime Madge became well known in Western Australia’s courts and papers as a somewhat comical figure – always in trouble, but never lacking an imaginative excuse for her exploits or a witty reply for a local magistrate. However, the more than twenty years in which Madge travelled around and around the Australian criminal justice system, appearing more than a hundred times and gaining more than seventy-five convictions, the words she spoke there are testament to something more than frivolity. Madge’s outbursts, the cheek and humour shown to the court was indicative not that she was unconcerned by her situation, but rather that she considered the police, local magistrates, and the establishment to be. Going to court for drunkenness and disorderly behaviour, peppered with the odd theft, violent outburst, or criminal damage, was the only anyone seemed to take notice Madge Foster, her difficulties, and her very evident need for help. In a time when women were so often dismissed, undervalued, and underrepresented, it was the only venue in which her voice could, or would, be heard. Many of Madge’s offences, and her appearances in court, were cries for help in which she highlighted her problem with alcohol or the futility of her repeated incarcerations. Occasions in which she pushed against the system with all her might, hoping, surely, for a more adequate response to her plight than the system ever had to offer.