Old Dogs, New Tricks

Female offenders were nothing if not inventive. The crimes of women in Victorian England could be both ordinary and extraordinary, from child-stripping, hocussing, and fantastical frauds to brawls, drunkenness, and acts of utter desperation. As with any subject, the more we study the particulars of an offence – despite the individual players and nuances of circumstance – the more predictable certain kinds of crime become. We can begin to see patterns in the way women went about deceiving their peers and dodging the law. I’ve come to know that many violent altercations between women occurred after accusations of infidelity and slights over reputation were traded, and that too many infanticide cases share in common the tragic plight of the unwed and abandoned mother. Even what once seemed like audacious and unpredictable forms of theft are soon revealed to be repetitive and formulaic. Prostitutes who would pick up drunken clients in a pub and entice them back to a room with the promise of a final nightcap, only to rob them blind. Women who would lure children into darkened alley ways to steal their boots and shawls. Pickpockets that worked railway stations and busy thoroughfares.

After studying hundreds of cases and police court reports I have moments of feeling like I know all there is to know about how female offenders plied their various trades. It is always thrilling to find a well-timed case which reminds me that as much as I know, in the world of female offending, there is always something more to learn.

Coining was one of the most popular forms of property crime for female offenders in the nineteenth century. Women could be involved in the process of making counterfeit coins, but more often then not, their primary role was in distributing batches of freshly minted fakes into circulation. Those who uttered counterfeit coin, or ‘smashers’ as they were also known, did not need to be of a particular physical type or skill set. They did not need respectable clothing, right speech, or the confidence or wares to carry out long-term deceptions. All that successful utterers needed to do was to trade counterfeit coins for legitimate ones.

A counterfeit crown

A counterfeit crown

Victorian England was awash with bad currency, From Liverpool, to Birmingham and London, there were large networks of both male and female offenders who made and distributed bad money. The small number of female coiners we know most about were those captured by the police. They fall into two groups: those of who worked with poor forgeries – greasy soft coins, or those of the wrong colour or weight – and those who became greedy or lazy, trading their coins in the same place over and over again, or those who tried to trade a counterfeit too large in value for the small goods or service they were after.

Until recently, every case of female uttering I had encountered followed a familiar pattern. A woman, or sometimes a pair of women, working with small denomination coins (shillings, half-crowns, sixpences) would enter a pub and ask for a small drink. A half-quartern of gin, for example, might cost 2 ½ pence. She would pay with a bad shilling, and take the drink, and a sizable amount of change in return. If an utterer did the same at several establishments, by the end of the day she could find herself full of free alcohol, and with a pocket of legitimate currency. The same ruse could also be carried out in shops. Coins were exchanged at butchers and bakers for food, or at retailers for cloth or clothing. The trick to successful uttering was in exchanging little an often – not requiring too much change, or carrying out the same transaction too often.

Forgeries were easily missed in the bustle of busy Victorian pubs

Forgeries were easily missed in the bustle of busy Victorian pubs

Caroline Crick, however, was a rare example of an utterer willing to take bigger risks for better pay. Employing a clever double bluff, Caroline would accuse retailers and tradesmen of attempting to con her with false-coin, while passing off her own and making away with their good coins.

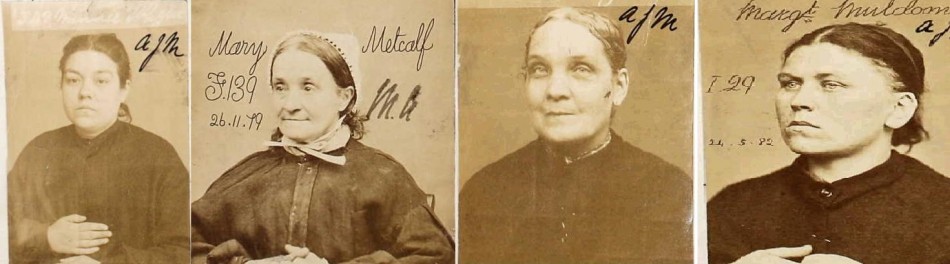

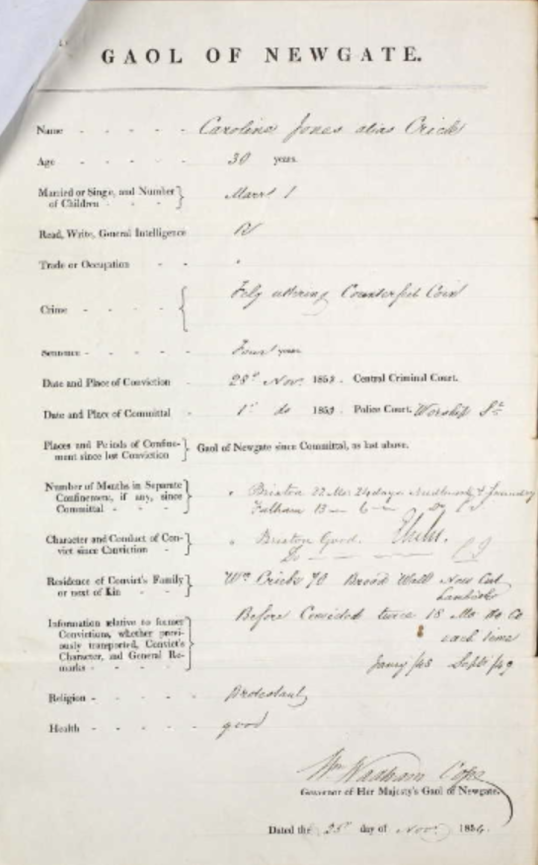

Caroline spent twenty years in and out of prison for various coining offences in the mid nineteenth century. Yet when it comes to personal details about Caroline, as with many female habitual offenders, are hard to track down. She was possibly born Caroline Jones, in London, around 1823. She lived in Lambeth and had two children with William Crick, and although they were never formally married, Caroline took Crick’s surname. Caroline also operated, in the early years of her uttering, under the name of Jane Banister.

Even Caroline’s earliest offences were much bigger and bolder than the average utterer’s. At the beginning of a two day spree in 1848, with one prison term already behind her, Caroline and her accomplice Rachel Levy visited a perfumer in Oxford Street just before closing-time. Caroline picked out a piece of sponge, priced at half a crown, and produced a five pound note to pay for it. The note was true currency, and the shopkeeper duly began counting out more than four sovereigns worth of change. Caroline was busy placing the change in her purse when her companion, Levy, spoke up, asking the shopkeeper the price of the sponge again. Levy remarked that she happened to have the right coin in her purse and she would pay for it. The five pound note was duly handed back to Caroline, and she returned the change. Levy paid the half crown and the two women left the shop with the sponge. It was only after the women were out of sight that the shopkeeper noticed that one of the returned sovereigns was not the original, but a false coin. The next day Caroline and Levy used the same five pound note to buy half a sovereign’s worth of wine. Caroline had received more than four sovereigns in change, but she called the barmaid back and rang one of the sovereigns on the bar saying she thought it sounded like a fake. She returned all of her change, reclaimed the note, and left the inn.

Next the two women visited a a confectioners and again, handed over the five pound note in exchange for goods and change, before finding the right coinage and returning the change for the original note, substituting a good sovereign for the bad. However, this time the shopkeeper noticed that one of the returned coins was a bad substitute and held the women while the police were called. Caroline and Levy were apprehended and brought to trial. Both were sent to prison for eighteen months. Had they been successful, the pair would have earned three pounds in two days, and very possibly more in shops that did not notice the deception or give evidence at the trial.

A counterfeit gold sovereign

A counterfeit gold sovereign

Shorty after her release from prison, Caroline went back to uttering. With a new accomplice, she no longer had the use of a five pound note, but instead a good sovereign, which she would ask shopkeepers to change the large coin for smaller currency, substituting one of the larger silver coins for a bad replica, and requesting a new one when she ‘did not like the look of it’.

Unfortunately Caroline was by then renowned as a coiner, she was being followed by the police. Officer Spittle went into the shop directly after her, and took the coin as evidence. Caroline, who had been known to the officer for two or three years, took on, he noted, a character while she worked. Dressed up in respectable clothing she would walk about the town gazing at the buildings and shops as if she were a visitor from the country. After conducting the same trick with at least one other retailer, Caroline and her female accomplice were taken into custody. As they headed away an officer nearby heard them shout to two men, who rapidly made away to Whitechapel. Caroline, it would seem, was part of a larger network of smashers circulating false coin in this way.

Each time Caroline was apprehended, the future materials with which she was supplied grew worse. Those further up the chain seemed unwilling to risk the loss of large amounts of legitimate currency (like the five pound note) or the loss of good counterfeits on an utterer who was so well known to the police. The amounts Caroline could deal in became smaller, and the quality of her forgeries poorer. She worked with cracked and chipped coins, those that could be snapped in half, and those for which the weight easily gave them away. This led to more frequent convictions and longer spells in prison.

Caroline Crick’s penal record

Caroline Crick’s penal record

As Caroline slipped further down the coining hierarchy, her offences became more common place. In her final trail at the Old Bailey in 1860, she was convicted, like so many women before her, of simply trying to buy goods with bad coin. Trading only in bad half sovereigns. Why Caroline had stuck for so long to a trade for which she was no longer profiting was answered in her statement of defence: ‘I hope you will have mercy on me on account of my poor dying husband and my helpless children. This shall be the last time I will ever commit a like offence; spare me this time from a severe sentence’. She was sentenced to ten years of penal servitude.

Caroline’s case is fascinating for two reasons. Her first offences give a hint of all there is still to learn about the practice of coining. Having looked at numerous cases of female coiners, hers is the first I have seen in which large quantities of money were exchanged, and in which slight of hand and deception were more complex than simply trading bad coins for goods and change. It is likely that Caroline’s case is rare precisely because those entrusted with changing high denomination good quality fakes had to be good enough so as to be untraceable. The materials and other people involved in this case -accomplices both male and female on the street, and those that made and provided the good and bad currency to work with – are very much on the periphery of Caroline’s story. However, they suggest a broader network of offenders at play, and a hierarchy which offenders could slip down as they gained convictions – and supposedly climb up if they succeeded too.

Cases like Caroline Crick’s are rare. However, when they surface not only do they add another vibrant thread to the rich tapestry of female offending, they are also a welcome reminder that even one hundred and fifty years later, one old dog can still teach another new tricks.

This post is with special thanks to Richard Ward who pointed out Caroline’s case while working with the Digital Panopticon’s new record-linkage interface.