‘Murder by a Midwife at Manchester’

For every crime, and every offender traced to the streets of sprawling Victorian cities, we capture a few moments of life unfolding before us on the page. In these instances we are offered a snapshot of a time, a place, and an individual.

Writing histories like these can be a complicated and difficult process. There are days of immense reward when a problem is solved or when a disparate trail of evidence comes together, like pieces of a jigsaw, allowing us to form a pleasing narrative for a long-pondered story. Then there are times when a sea of documents, names, dates, and events make us realise that even the best investigations can barely scratch the surface of the intricate web of ideas and experiences that shaped life in the past.

Recently the discovery of a long forgotten crime, by a long forgotten offender, was a stark reminder of just how fleeting our interactions with those in the past can be.

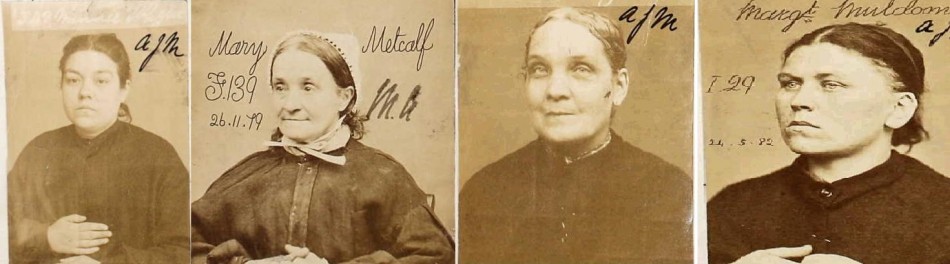

Ann Cartledge was the kind of woman who rarely takes centre stage in history. She wouldn’t be out of place in a Gustave Doré painting, although she would never be the subject. Many of us have probably read dozens of descriptions of her, and those like her, in the work of Dickens or Mayhew. Ann was old and poor, and to her social ‘betters’ (not to mention her observers in the 21st century), she was unremarkable.

Born in Stockport, in the 1820s, she married Thomas Cartledge, an engine fitter, and together the pair had four surviving children. Ann worked as a midwife. Unlike the modern profession, this occupation was not subject to formal training and practiced by local women for a network of their friends and neighbours. Knowledge of the services she offered was built up over time, and word of mouth was how she secured work. Like many other midwives, her duties could range from helping women give birth, to caring for women and helping around their homes after the birth of children, to the tending of sick children.

Other than census entries Ann would be virtually absent in the historical record, tending silently to poor women in the inner-city slums of Manchester, except for a seemingly out of place conviction cluttering her narrative – a murder.

In 1877, for a period of three weeks, Ann had been attending a thirty-four year old widow named Elizabeth Coleman. Whilst Elizabeth had been acting as a housekeeper for a man named Crompton the two formed a relationship and Elizabeth became pregnant. Ann was called to perform one of her little advertised but clearly well practiced trades – procuring abortion. Witnesses testified that Ann gave Elizabeth a ‘potion’ to bring on a miscarriage and then went upstairs with her to procure a miscarriage by ‘other means’. In this case that involved the use of a feather quill and a long piece of wire. Soon after, Elizabeth miscarried her child. Although little evidence remains for historians of such medical procedures and the women who went through them, we can broadly assume that this is in part because of the common nature of such events, the coming and goings of the midwife must have been a regular feature of life.

Unfortunately for Elizabeth Coleman her ordeal did not end there. From the time of her miscarriage Elizabeth was reported to be in ‘great pain’ and suffering from abdominal pains, and symptoms like that of scarlet fever. She died just a short time later. A post-mortem of her body found her womb to be in a ‘very disorganised state’. Inflammation and gangrene made it difficult for the examining doctor to be sure of the severity of violence inflicted. Shortly before her death, Elizabeth had testified to her experience in front of a policeman. Ann Cartledge was quickly identified and arrested. Ann was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Her sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment, and she was released after serving six and a half years in prison.

As historians, we can understand that the frightening and painful death of Elizabeth Coleman was a tragedy for both victim and offender. For Elizabeth Coleman (and sadly too many women like her) contemporary gender ideals placed unrealistic expectations upon her, and restricted her rights – in this case to her own body. For Ann Cartledge, Elizabeth’s death resulted in the loss of her home and her liberty. Thomas Cartledge died whilst she was in prison and upon her release the widowed Ann spent the remainder of her life living on the support of her children. Ann, in her own words, made plain whilst in prison that she ‘was innocent of any bad intention’ towards Elizabeth. Women who carried out the services of midwives mostly did so to earn a living, and to help women for whom there was legally or financially no other option. Although the records to prove Ann was not only a one time offender do not exist, and never have, it is only too likely that this was not her only offence.

The practice which led to Elizabeth Coleman’s death was just another day at work for Ann Cartledge. Not only can we assume that over the years that she practiced that Ann was responsible for procuring many miscarriages (an offence in itself during this period) but also that Elizabeth was unlikely to be the first or only of her patients that died from this unsafe and unsanitary procedure. However, the length of time Ann worked this way, how many women Ann saw, how many deaths Ann caused – and the impact all of this had on her relationship with her peers, her community and her neighbours, are avenues of inquiry that remain forever blocked to us. It is instances such as this that we are offered a prudent reminder that most of us are, at best, repeat tourists to the past, barely aware of the lives risked and lost, property traded, and secrets buried all around us in the slums we think we know so well.

Very interesting story. Also I am attempting to see if this family is connected to my CARTLEDGE line and wonder if it would be possible to exchange some more information.